Work Text:

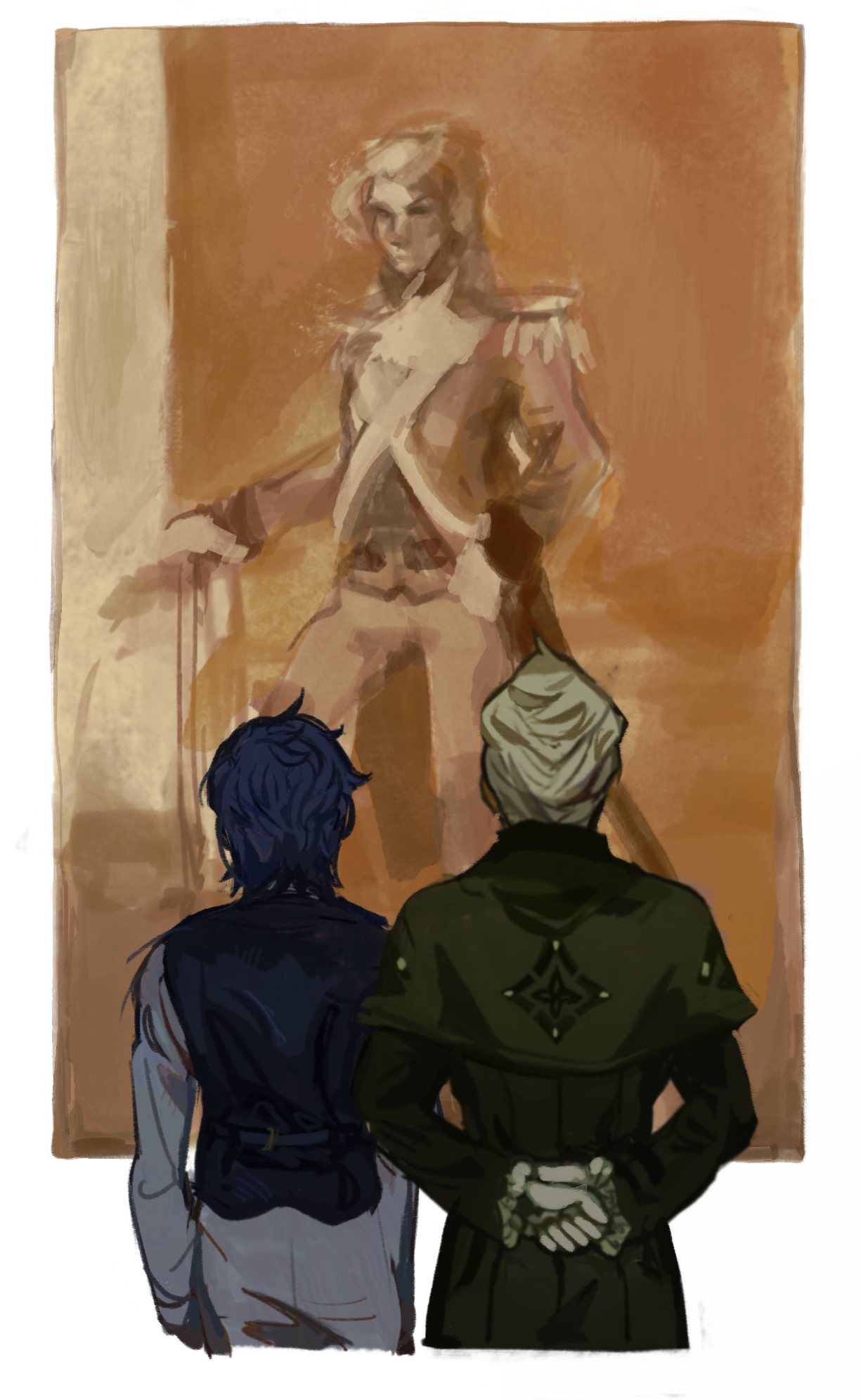

Lord Klint van Zieks had been a tall man, but never a well-built one. Gangly in a delicate fashion that had put Mael in mind of a young Abraham Lincoln whenever he wore a tall hat. Looking up at the sketch, Mael can tell that the painter has intentions of generosity. Though not by much—there’s only so generous a painter can be before the subject becomes unrecognisable.

Mael has chosen his portraitist well. A bit of extra muscle, extra presence, is perhaps a clever call. Unrecognisability defeats the purpose.

From the foot of the artist's ladder, he inspects the beginnings of Klint van Zieks. Eight feet tall and pre-rendered in shades of lean sepia. Posed nobly, like a conquering hero, amid foliage and crumbling columns—a man who had never existed in a place that had never existed either. A construction. A painted doll in a model room, a still life more than a portrait.

It's perfect. There’s just enough of him to strike that vital chord in his brother’s heart, and not a bit more. It’s not the man himself, after all, that Mael had ever intended to portray, but a posthumous collage of the best of him. A glittering sheen of him, a saint remembered falsely in death. That’s what Barok needs to look up to right now. He needs to internalise it, smooth it over the top of his own memories. He needs to forget his brother as he’d truly been.

Mael won’t say well done, not when nothing’s been done yet. He taps the ladder with the head of his cane. “Carry on.”

“Yes, sir.”

And then he clasps his cane in his hands behind him, and he takes a few ponderous steps back. He needs to: not many things tower over Mael Stronghart, but this canvas stands as high as the office ceiling where it’s to hang.

He gazes up into Van Zieks’s shadowed face.

He’s arrested for a moment by the look on it. Some of the painting may be pure invention, but this expression had been his. The sharp eyes, the drawn, arched brow. The haunted, distant anger. It’s been captured impeccably even in the monochrome. The emotion in it colours the portrait entirely.

A newspaper from three years ago is pinned near the top of the canvas—Barok’s. Since childhood he’d kept every mention of his brother in print. It was the closest thing to documentation that Mael could find of this face that he’d seen Van Zieks wear so often, this expression he’d requested specifically. A photograph snapped of the defeated prosecutor out front the Old Bailey, after a crafty extortioner had walked out a free man.

How do you stand it? Van Zieks had asked Mael in the hours afterward, drunk on Scotch whiskey in his lamplit office. All these years you’ve been prosecuting… When you do everything right, and even still…

Mael had considered this, looking down into his own full glass. Faith, he said eventually.

Van Zieks laughed. A bitter bark. In God?

No.

The law?

No, Mael had said. In myself. That, in time, I will find a way.

And everyone who’s hurt? asked Van Zieks, after a long, heavy pause. In the time that it takes?

True progress cannot be rushed: this was a lesson Van Zieks had never learnt. Mael had shaken his head.

Avenged, he’d said.

It was around that time that Van Zieks had truly begun to understand his powerlessness within the confines of the law. Around that time Mael had almost had hope for him. He’d seen the shining young golden boy tarnish and dull over the years. Seen his eyes darken into the sorrowful, vengeful pair that overlooks them now. He’d thought, perhaps, that Klint van Zieks could have handled what it took to change things.

He'd been proven grievously wrong.

It’s the Klint van Zieks of those more promising years that Mael needs to capture. The look that he’d worn then is the one that needs to be immortalised. Barok will look up into this face every single day. In those eyes he will see his brother’s dream unfulfilled, and he’ll be inspired all the more to soldier on.

Mael turns and glances toward the back of the room. Barok van Zieks stands there, a look not unlike his painted brother’s on his sharp, pale face.

Barok does not move as Mael strides over, doesn’t even turn at the slap of his soles on the stone. He doesn’t look over as he stands at his side.

“You’ve been spending a great deal of time here,” Mael says. “Overseeing?”

Gregson has been keeping tabs on Barok’s movements for him. Mael hadn’t hoped for such measures to be necessary, but Barok van Zieks is not a well man. Though rage had carried him through Asogi’s trial, it had only been able to carry him so far beyond: in recent months, he’s been walking about half-dead. Unsuitable for the Reaper of the Bailey—unsuitable for London. Looking at him now, Mael knows he should have foreseen this. He had engineered the Reaper’s mythos such that Klint van Zieks and his yearning for justice lay at the root of it, in a way so fundamental that he hadn’t believed it possible for Barok to ignore, however…he’d underestimated the fundamental melancholy at the root of Barok’s being.

A visual reminder might be more effective. Mael hopes it will be. He would hate to resort to more forceful methods of control. It’s a far less certain game, and far more exhausting. He has a great deal to be getting on with as the Lord Chief Justice, after all—he can’t be spending all his time making sure Barok van Zieks does what he needs to.

Perhaps his brother can do that for him.

“I wouldn’t call it overseeing,” says Barok quietly.

“It’s only natural that you would,” Mael says. “It’s a perilous thing, is it not, to put something so important in another’s hands?”

“…Yes. I suppose.”

“Are you pleased, thus far?”

“Yes,” says Barok. He still cannot look away from the canvas. “He’s very talented. The Thorndyke Academy trains their students well.”

A more prestigious artist could have easily been found elsewhere, but they’d agreed a bit of patriotism felt appropriate. “They do.”

“The depiction is acceptable?”

“More than acceptable.”

“And yet you’re conflicted.”

Barok’s lips flatten together, reluctant. “…On the painting itself? Not at all.”

“And otherwise?”

He sighs. His eyes leave the painting for the first time as he turns his face away. “It’s so grand, Lord Stronghart… It’s—it’s what he deserves. But do you really think it appropriate, sir? For the office?”

“Whyever wouldn’t it be?”

“…Are you sure it’s in good taste?”

“Good taste?” Mael turns to him, brows raised. “To honour your brother, in the office where you carry on his mission? I could hardly think of better.”

“In any other man’s office, perhaps…” Barok replies. “But the Reaper of the Bailey’s?”

…Ah. “I see.”

“You’ve heard the whispers, sir.”

The plan had fallen into his lap nearly complete. Mael had never been a believer in fate, but the stars had aligned over the Reaper so neatly that it had felt perfect, intentional—meaningful. A spectre was a far more untroubled assassin, a grieving brother a far more obedient figurehead. The death of Klint van Zieks had been the missing piece.

He shakes his head. He must maintain skepticism. “Ghost stories,” he says. “Nothing more.”

Of course, Mael knows that Barok won’t believe him, not truly. Everything has always hinged on that. But he must also give Barok something to disbelieve, as he gives him something more hopeful to believe in. Lord knows that’s just as motivating.

“…Be that as it may,” says Barok, “are we not beholden to the public?” He swallows, takes a moment to summon his words. “Perhaps to us, my brother died a hero, but to London… He haunts them, sir.”

Quietly, Mael sighs.

“Is it not…uncouth?” Barok asks. “To memorialise him so grandly, in such a place?”

“Lord van Zieks,” says Mael after a long moment. “You prosecute to serve the people of London, in the way that you know they must be served. But that does not mean that their inane gossip must be paid attention to.”

“I simply don’t wish to appear as if I mock the idea.”

“The idea that they mock his memory with?” Mael scoffs softly. He looks down at Barok’s face, still bent away. “Do not let your brother be reduced to a bogeyman, Lord van Zieks.”

Barok pauses. He lifts his head, turns his face up to him.

Mael looks back deeply into his sunken eyes.

“No man in a hundred years has done more for the law in London,” he says, slowly, firmly. “Lord Klint van Zieks was a great man who fell in the line of duty, and now it falls to those of us who truly knew him to preserve his memory.”

Barok closes his eyes for a moment, then looks back up to his brother.

“…It is what he would want of me,” he says. His voice is thin. Weary. “To…remain strong. To do what I must.”

Mael watches him for a moment longer.

Barok van Zieks did not know his brother at all. Barok had known his brother as Van Zieks had wished he’d been—the brother he had allowed Barok to know. That brother would have wanted this of him. But Mael had known him, and he knows that such a cold pursuit of justice is the last thing Klint van Zieks would have wanted for Barok. That his greatest wish for his brother had been to never discover the path he’d walked, and certainly for him never to follow it. Never to lengthen it himself. Never to accept its lengthening.

It had been the only thing Van Zieks had asked of Mael. The man had been at his mercy, and all he had cared for was his family’s admiration. To betray the image he’d created for his brother would have been worse than arrest, than trial, than execution.

Mael looks up to him again, and he can barely see that desperation in paint.

In a way, the image that Van Zieks himself had created for Barok and this image that Mael has begun creating are nearly indistinguishable. Both bright and shining, noble, hopeful, guiltless. Both born of a desire to guide Barok’s future down a preferred path. Mael and Van Zieks had both seen his devotion, and they had both understood that he would become whichever idol was presented to him. They’d seen that same opportunity.

But Van Zieks’s false self had been created from a place of shame, and Mael’s false reflection of him from a place of hope. Of faith, like he had told Van Zieks so long ago. Faith that Barok van Zieks can do what his brother—living, anyways—could not. Could never do.

What have I done to you? he had asked near the end. Begged, on his knees. Not in Mael’s old office where they’d spoken all those years before, but the new one that his actions had handed him.

Done? Mael had replied. You’ve done nothing to me.

Then—my God, why…

Mael had reached out to rest a hand on Van Zieks’s trembling back, had looked down into his furious, flaming eyes. It’s what you can do for me, Lord van Zieks, he said. For yourself. For all of us.

Van Zieks had spat at him.

Mael had lifted his handkerchief and wiped it away without a word.

He rests his hand now at Barok’s back. It’s a gesture Van Zieks might have set his dog on him for, but neither he nor his dog remain to take issue. Lord Klint van Zieks remains only in the forms that Mael has built him.

As the painter begins to lay down the first strokes of colour, the shadows around Van Zieks’s triumphant feet, they watch together in silence.

It’s glorious, the memory that Mael Stronghart has made for him. The sort of legacy any number of more deserving men could only hope for. He’s a martyr, an angel, a soldier and a symbol, when in life he had been little more than a coward. In death…in death he can do more good than he ever could have done alive. Death frees him from the heart that had held him back.

As Mael looks up to him, he can’t help but feel generous. Benevolent. Everything he’s done has been an unearned courtesy to the man who’d failed London. A gift to him. But—more profoundly than that, a gift to his brother. Through his brother, a gift to the people.

Mael opens his watch and takes a glance from the corner of his eye.

“Come,” he says, low-voiced in Barok’s ear. “I think you’ve spent enough time here today.”

furaleny Fri 10 May 2024 10:31PM UTC

Comment Actions

oh_help Fri 17 May 2024 09:54PM UTC

Comment Actions

Mnemosyne_Elegy Sat 11 May 2024 11:13PM UTC

Comment Actions

oh_help Fri 17 May 2024 10:09PM UTC

Comment Actions

ChiiChuu Sun 23 Jun 2024 07:43AM UTC

Comment Actions

oh_help Wed 26 Jun 2024 06:35AM UTC

Comment Actions

EatYourSparkOut Thu 25 Jul 2024 03:22AM UTC

Comment Actions

oh_help Fri 26 Jul 2024 11:08PM UTC

Comment Actions