Work Text:

September rain lashes the tinsheet roof of the chapel. Aziraphale raises his voice a little and tries to believe in the words falling from his mouth. His bootheels squeak on the pulpit floor; pain claws at his leg and between that and the rain, he misses a line of the reading.

Falters.

Stares down at the war-torn faces in front of him, and their not quite judgmental silence. Like most congregations now, his is impossibly unbalanced; women and boys and old men and a gaping wound of empty pews in the middle of it all.

The silence, edged in by rain, stretches until he thinks he can hear screaming in it.

His lips are too dry, his mouth clamped uselessly closed, and the people that are left, the remains of the ones he was meant to care for, are shifting in their seats again.

The words are dancing in front of his eyes. Not dancing like he used to at summer fetes; running, fleeing, a parody of dance in that twisted way men dance when their partner is a bayonet or a bullet.

He slams the book closed as though it would shut down memories; jumps to the old prayer. Their voices take over where his fails.

‘Our Father, who art in Heaven…’

And doesn’t answer to thy name…

‘Give us this day our daily bread…’

Once the rats have finished with it, once it’s turned to slush and pulp in our pockets, you’ll give it to us…

‘On Earth as it is in Heaven…’

And if that’s what Heaven’s meant to be like, I want no part of it…

He lies to them as best as he can, with a smiling face, and a calm tone. Better that they never know, the ones who never saw it.

Aziraphale pretends exhaustion afterwards. Sits on one of the bare wooden pews with his bad leg stretched out, and shakes hand after hand, and lies.

Yes, he’s fine, thank you.

No, he’s doing very well in what used to be the Manor House, no need for any assistance. Of course it hasn’t been the same since his father died but he couldn’t justify needing staff when it’s only him in there.

No, the children are doing well with their reading at Sunday School, and that one isn’t quite a lie because he likes watching them learn.

He asks after people, as best as he can. His memory seems to be shuttered behind something at the moment; obscured by drifting clouds of smoke and ordinance flares. The names trip him up, get muddled, and he’s vaguely aware some of them are looking at him with concern.

‘Someone saw that black horse on the sands again yesterday,’ Newt says.

Newt’s one of the lucky ones. Too young to have been called up. Unlike a lot of the others, he doesn’t seem to feel he missed out on anything.

‘Black horse?’ Aziraphale queries. Tries not to think of the black horse drowning in the mud before he could cut it free from its traces. He wonders, sometimes, if there’ll ever be any words that don’t have France underscoring them, a parade of horrors in their wake.

‘Oh, you know,’ and Newt laughs. ‘The kids all say it’s a demon. Got backwards pointing hooves and red eyes.’

‘You sure that isn’t just one of Davey’s colts, love? You know the dregs he’s breeding,’ Tracey asks with a smile and there’s a sudden outburst of good natured teasing and laughter.

Davey’s the only one with horses left around here; all the rest went to the army and the lucky ones are dead.

Aziraphale shakes his head. ‘You know what the children are like, Newt. Full of stories at the best of times. One of them saw something, and it’s turned into this. Tell them it’s nothing to worry about.’

He gets some doubtful looks as they all file out but he’s used to that now. Used to his own expression in the mirror; a scraped clea face and blond hair shorn military short still, nothing he can recognise of himself.

**

The Manor House is too big for a man on his own, and what used to be his parents’ wing is a haunted place, anyway. He keeps that shut up, keeps the door locked as though that might reach back in time and keep everything away from him forever.

The front room’s burning with a fire he’d laid himself, and the electric lights flicker into life when he thumps them. There’s a mound of packages inside the door, wrapped in brown paper and string and for a moment, there’s the old and pointless dread that they’ll be uniform items, jams, cigarettes, the detritus sent to the Front, and someone will be expecting him to start it all over again.

But it’s books, sent down from the last auction in Cardiff, and carefully dropped off by Leslie the postman who knows Aziraphale of old and knows that he’d rather have the books safe indoors than worry about his privacy.

Normally, a new delivery is a joy. Now, his hands are still trembling from the service and the noise of the rain on the slate is enough to drive him mad. He won’t be able to focus, even if he does try and look at them.

There’s food around if he wants it; a bottle of wine hidden under a litter of everything else and it sings, siren sweet, of peace and oblivion. He stares at it, wondering.

Remembering.

He wonders, sometimes, if his father had drunk. Or if that had been one of the vows he did keep, unlike the marriage ones. Aziraphale hadn’t drunk until he’d enlisted; told himself it would be different when he was home again.

Well, he’d been right about that, at least. One small shining achievement in the wreckage of everything else.

Everything had been different since he got back.

He opens the wine. Slams it down in frustration and suddenly the house is too much of a prison, large though it is. Full of old voices and the dark.

Outside is darker still, of course. The stars are veiled, the moon in mourning clouds of rain. But he’s known these paths all his life, even if some of them are now paved for motor vehicles.

Left, down the hill. Past the dim warmth of the pub. Head uphill, past the softly dreaming cows in their byre and the cat that twines between his legs for a moment, hoping for and receiving kindness. Out past the humans’ domain and up into the wilderness of the cliffs, where the rain thunders across the Irish Sea to rend whatever it can reach and the old injuries snap and bite up his leg so he’s limping as he walks.

The headland is a wasteland of stunted plants, the grass soft with sand. He finds the most sheltered spot, which is hardly a shelter at all, and stares out into the blackness.

Waves break in their regiments on the shore. Muttering about freedom and then collapsing with the effort. Their white froth bleeds out against the sand.

An hour. Two hours. The cold and the wet is a physical thing now, another old dance partner wanting a turn with him, but this one’s easy to ignore.

Is that movement on the beach? Aziraphale squints, wipes water from his eyes, and looks again. Jet against ebony, something moves.

He watches it for a while. It looks more like a horse than anything, but then he’s had three years of seeing things no humans should see, and no longer believing in the things he once did.

It doesn’t leave room for curiosity. Just existing.

Aziraphale goes home. He sorts the books and marks them to repair or to resell. He prepares for next week’s sermon and tells himself it will be different; that he’ll be able to believe in this one. He lectures Adam and Brian on their lessons after school, and doesn’t think about the black shape at all.

**

They can’t find him when it happens, although it’s a Sunday. He’d left Chapel as quickly as he could and just… walked. Walked and walked and shouldered his way through the rain and made promises to himself that he was going to go home and update the records.

But when he does head home, it’s getting dark and there are people shouting and it takes Adam running up and grabbing his arm, yelling ‘Mister Fell? Mister Fell?’ Before he realises something’s happening.

The police have been called, of course. But that meant Gabriel who has a car, driving into town to call from there and waiting for them to arrive.

So there’s a gaggle of people on the beach, with Anathema who used to be a nurse crouching over the body and Newt trying to keep the children away.

‘I’m glad you’re here,’ she says as Aziraphale hurries across the damp sand. ‘I didn’t want to move him, but I think we’ll have to. The tide…’

He glances sideways at it, unwilling to look away from the body. It fascinates him, in the old sense of the word. He thinks this must be what Faery enchantment would be like; sick horror, wanting to look away and not being able to.

‘I think we’ll have to,’ he agrees. The tide’s lapping close by, waves exploring further each time.

He doesn’t want to touch the corpse. Cringes away from it.

But he was a soldier once, and a preacher still, and there’s people in the crowd looking to him for answers, so he does it.

Grabs a couple of them who he knows have livestock, and he thinks they’re all trying to pretend it’s just a carcass, just something to move across the yard and leave for the knackerman.

Black hair flips down across a blue eye, suddenly aping life as the wind blows.

He tries not to look, tries not to feel.

The sand around it is churned to chaos with footprints and water ebbing in; he thinks, for a moment, there’s something that looks like a hoof print and then he shakes his head and focuses, again, on moving the body.

Aziraphale drinks the wine when he gets home.

**

The police come and visit him, of course. Two older men whose names he doesn’t quite catch, who seem to fade in and out of the village without really mattering. They’re not sure who the dead man was. They’re not sure what happened. They haven’t really got any ideas.

Aziraphale shrugs. He hasn’t either, and there’s no-one missing who shouldn’t be.

Well, half the village is missing of course, but that’s just how it is now. Empty pews and empty houses, the scratch-scratch of the stonemason’s tools on the memorial.

‘I’m sorry I can’t help you more,’ he says in the end and they both shake his hand as though he’s done something useful.

Rumours swirl around like leaves, both thrown around by careless children. It was a sailor, washed ashore. It was a lover’s quarrel and the man was from Cardiff or Newport or Liverpool. It was a jewel thief and Scotland Yard were looking for him; that one makes him smile and he lends Adam some Sherlock Holmes novels as a distraction.

‘It was the black horse,’ is another one of the rumours and that one creeps in like mist settling, seeming to start from everywhere all at once. Until half the village is saying it, half the congregation are talking about it after the service, and the children, laughing in the street, stomp their feet like hooves on the stones.

They let him bury the man a fortnight later, as September eases into October. Blackberries hang thickly around the grave, a corner plot of land unspoken for by any of the local families.

Aziraphale talks about Heaven in the service and tells himself he believes every word of it. Admits to himself, as the earth scatters back across the cheap wood, that he’s lying.

**

The moon is a thin ghost of a thing, the faintest crescent hanging over the sea. The waves, ever forgiving, have cleansed the beach of blood and horror and replaced it with a high tide, the curious nosing of fish and the slow creep of seaweed.

Aziraphale sits and wonders how much blood it would take to turn it red. Not rivers; he’s seen it happen to rivers. But the sea.

His fingers ache from handling the shovel. His bad leg is a symphony of pain from digging.

The darkness moves again, swirling down by the far cliffs and this time, he thinks he does see something move. Something coming closer, more like a horse in gait than anything he can think of, although horses shouldn’t move in that wretched, lurching fashion (they do, they have done, he’s seen it and it’s there in the file catalogue of his mind as to what causes it, however quickly he tries to skim past those pages) and it’s dark, impossibly dark, in colour.

He tracks it by watching the waves it blocks out.

Closer and closer, and it halts and raises something that must be a head and he feels, suddenly, as though he’s looking at the loneliest thing in the universe.

It calls to him, that isolation.

The cliff path slips under his boots, showering rocks down in front of him and they dislodge other rocks so his arrival on the beach is heralded by a shower of them hitting damp sand. The creature turns to look at him.

And he sees…

He sees…

Aziraphale blinks.

He sees intelligence, understanding, peering back at him. Curiosity and wonder and fear, but he considers the word creature again for a moment and then the word ‘person.’ That seems like it might be a better fit.

He hurries, as best as he can. He’s never been built for running, even when he was in the Forces, and eighteen months with people trying to force tea and biscuits on him every time he visits their houses for work hasn’t helped.

The dark horse looks at him in silence and he approaches in silence. So silent, he thinks, they may as well both be in another world.

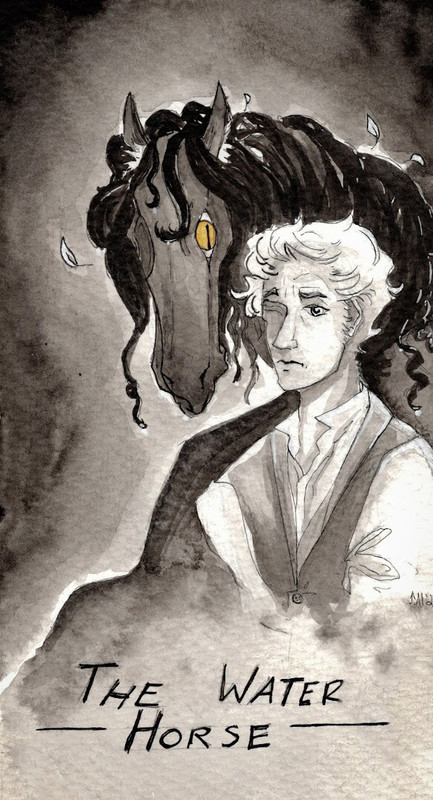

It is a horse and it isn’t.

Well, he’s a priest and he doesn’t believe in God so he’s well used to living contradictions.

The coat is darkest black, darker than any horse he’s seen. Even the black horses in London who pulled the great hearse to Westminster with the Unknown Soldier, when he’d stood in the rain all day and told himself it was worth it.

The eyes are starfire, sunfire, liquid gold, daffodils in the sunshine. The most beautiful colour he’s ever seen, he thinks.

And the legs, the grotesque, twisted legs… the hooves and fetlocks are all of them set backwards, reversed. Twisted, the tendons and sinews twined like a snake and yet… he’s seen twisted things beyond counting, beyond sanity. At a second glance, he realises these are right. Are correct for what he’s looking at.

The head, disturbingly equine, drops to look at him. There’s a hint of forelock dropping down between the eyes, an impossible dark red mane like brushed silk arching down the neck.

Aziraphale stares at the being, and is not afraid.

‘Do you have a name?’ He asks at last, although he can’t imagine why he thinks it should speak.

‘Crowley,’ comes the reply. It sounds so like running water he doubts his hearing.

‘Sorry?’

‘Crowley.’

A pretty name, he thinks immediately and then shakes his head at the strangeness of it. He’s not entirely sure he heard that reply with his ears rather than his mind.

‘I’m Aziraphale.’ The rest of it, the job title he can’t escape, the surname he’d been tied to by an accident of birth, seem meaningless out here in the dark.

‘Aziraphale? Pleased to meet you, Aziraphale.’ Is that a touch of humour there, amusement sparkling like dew on flowers? He wants to believe it is.

‘What are you…’ he bites that off, unsure if there’s any polite way of finishing it.

‘What am I? Or what am I doing here?’ Crowley shakes his head, scattering water drops from his mane. ‘I could ask you the same thing. Your kind should be asleep.’

‘I don’t sleep very well,’ Aziraphale admits. ‘And I was busy, all day.’

‘Your kind are always busy, doing things. And fighting, from what I’ve seen. You fought so much you broke our world into ruins alongside yours.’

Aziraphale drops his head, looks away. The words wash shame and anger in their wake, bringing up the old ghost feel of a rifle in his hands. ‘I’m sorry.’

A soft, mostly wordless noise that he thinks might be acceptance.

Crowley stares at him a moment longer. ‘You know one of your kind was killed here recently? It’s probably not safe for you to be here.’

‘I live here,’ Aziraphale points out.

‘So? Homes aren’t safe, are they? That’s just what you tell the younglings so they’ll sleep alright, but you don’t look young enough to believe that.’

He stares at Crowley for a moment, with fresh eyes. Sees the unevenness in his stance, foreleg pointing awkwardly and hips twisted. The uneven tilt of his head.

‘What happened to you?’ He asks in a hurry.

A sardonic toss of the head, thin excuse for a forelock fluttering around his ears.

‘Asked too many questions. Got some answers. Unfortunately, the answers were mostly ‘we don’t want you here anymore’ and ‘fuck off out of it before we kick you out.’

He wants to ask more, to find out more. Doesn’t know if he can cope with the remains of his worldview shattering apart like that.

‘I’m sorry,’ he says instead. ‘That seems… unfair.’

‘Yeah.’ A long pause, when they both listen to the waves and the slow scrape of pebbles. The emptiness of the wide night around them.

‘It was unfair when my cousin killed that human of yours as well. Beez was looking for me, and I think he got caught in the way. Beez always did have a temper.’

‘There are more of you?’ And he realises as soon as he’s said it how stupid it sounds.

‘Not here now, no,’ Crowley says and his head hangs as he speaks. ‘They’ve all gone back.’

Aziraphale stands with him in silence, and they watch the stars and the waves together. Eventually he rests a hand on Crowley’s neck, and their silence is deeper than memories.

**

Aziraphale tries to keep himself busy for the next fortnight. The leaves are burning gold and yellow, the trees starting to turn into silhouettes against the sky. The swallows in his eaves leave an empty nest and a mess of debris on the floor, a ringing silence in the mornings.

People come and ask him about the dead body; it’s the only thing that’s happened here since the War. He tries to get them to leave and goes back to staring at books, stitching together pages and spines as though he might be able to stitch lives back together so easily.

He doesn’t go down to the sea again.

Tries to convince himself that it was a dream, a fever, anything. That he can’t remember the feel of Crowley’s coat, cool velvet under his hand.

It lasts until the day he’s meant to be preparing for the harvest festival, when people are bringing offerings and the horses and tractors alike are standing at ease after the brutal work of the last few weeks. The village thrums with tiredness, with relief that the rain’s held off. Haystacks cast shadows across the fields, and the chapel is decked in barley and wheat sheaves.

There’s always a surplus, always enough to be given out amongst those who need it, and it’s those that he’s sorting out now.

He’s strong at least, has always been strong. Not much of a gift, but something.

A hessian sack of oats. A handful of cabbages. A bag of potatoes and the sack breaks, leaks rotting pulp out across the floor and his shoes and there’s a worm in it, writhing and twisting and it’s not rotten veg, it’s not the muddy gravel outside the chapel, it’s Flanders and…

He’s sick before he can get away, retching and gasping for air that stinks of rot, gagging until his throat hurts.

The cliff path offers sanctuary of a kind; he finds himself hurrying along it with no conscious thought. It’s almost dark when he comes back to himself, high on the highest cliff. Still trembling, still shaking but at least knowing what country he’s in now.

He goes down to the sea again, and recounts Masefield’s poetry as he goes. Crowley’s there, stood up in the lea of the cliffs, greeting Aziraphale by name as soon as he appears.

He tells Crowley that poem; laughs at his expression of fierce concentration and then utter bemusement. ‘But your kind can’t live in the sea. Why do they want to go there?’

‘A lot of us can’t really live on land, either,’ he says slowly. ‘We all think we’d be better off somewhere else. Anywhere else.’

‘You sound different today,’ Crowley says in reply. ‘Sad.’

‘Bad… bad dreams. Or what do you call a dream when you’re not asleep?’ He feels, somehow, Crowley won’t judge him as the others would.

‘I know what you mean,’ Crowley says. ‘I don’t know the word but I know what you mean.’

‘Do you dream?’ Aziraphale asks after a moment.

‘I try not to.’

It sounds like an echo of his own thoughts.

They spend the night on the beach, mostly in silence.

**

By the time Aziraphale gets home, the worms have slithered off to wherever they need to be. The potatoes, aired out, have lost the reek of death and he can’t imagine now that there was ever anything wrong with them to horrify him like that.

He eats a breakfast he doesn’t want and allows himself to fall into bed once his eyes are stinging with exhaustion and his legs are trembling. Perhaps it’ll be enough to let him sleep without dreaming.

It isn’t, of course. The sun creeps round the blinds, and reaches down into his dreams; it’s enough to disturb him, again and again until it’s only a thin shadow of sleep. Teasing him with peace for a moment and then snatching it away again, throwing him back into dreams.

‘You dream loudly,’ he hears someone say and glances around to see Crowley standing neck deep in the sea.

‘What are you doing here?’ He asks.

‘I thought you called? I didn’t know humans could do that.’

‘I wasn’t doing anything,’ Aziraphale protests and then slides out of the dream into actual proper wakefulness. He thinks he hears a noise on the wind; a high, bugling neigh like a stallion’s call.

The village seems more like a prison that week, or perhaps it’s his own mind feeling like one, turning the late sunshine into bars. He finds himself reading Wilde one evening, the Ballad of Reading Goal, and has to choke down the urge to throw the book across the room.

He’s almost surprised, when he’s getting dressed for work on the Thursday, to realise that he doesn’t have a jacket left where he hasn’t worn the sleeves away at the wrists, fretting at them with his finger tips.

How long since he’s actually looked at his wardrobe? Perhaps he should go up to London again, find some of the places he’d known as a young man and come back with some different clothes at least.

It seems like too much effort, and besides, the old shirt is comfortable like little else is.

Anathema greets him as he’s heading back from his home visits, waving him down so he pulls over and stops.

‘What can I do for you?’

‘You’ve heard the rumours, haven’t you? About the dead man.’

He’s only left the house for work this week, and the conversations there have been the usual ones. Harsh, upsetting ones about end of life, or practical things like witnessing some papers being signed; he knows there’s been babies born and couples married here since he came back but the joy of officiating for them doesn’t seem to have left a mark on his mind.

‘No rumours, no.’

She raises an eyebrow at that, a slight challenge to his authority. Aziraphale finds he doesn’t care; a priest without a god can’t be much of an authority to anyone, can be?

‘The kids are still on about a demon thing down on the beach. And more inland, there were some odd tracks found in some fields.’

‘There aren’t any such things as demons,’ he says, and it probably sounds as shaky and false to her as it does to him, because he’s met demons before and they wear all manners of uniforms or suits in high up offices and do a fine job of passing for men.

‘No? That isn’t what you preach.’

Aziraphale shakes his head, mutely.

‘Something killed that man,’ she says after a moment. ‘And you’re spending an awful lot of time out on the cliffs. Did you see anything?’

‘No! The police haven’t found anything out. For all we know, he was from miles and miles away, and wasn’t killed here but the sea swept him in. You know as well as I do that the currents do that.’

He hurries away before the conversation’s run its course.

**

‘Do you know what happened to the man?’ he asks Crowley directly at their next meeting. ‘I know you mentioned your cousin but…’

‘The dead one? I suspect he met my cousin when I wasn’t looking, from what I heard. They were… very angry.’

Aziraphale doesn’t dare admit to himself that he’s relieved it was nothing to do with Crowley. Or that he’s instinctively, atavistically frightened of the idea of more unknown, nightmare born creatures wandering around.

‘They probably won’t have stayed very long,’ Crowley says, as though picking up on his nerves. ‘Your world is…overwhelming at times. Most of us just want to go home.’

Aziraphale wonders what home might be for Crowley. What it might once have been for him; he’s fairly sure he doesn’t have a home now.

‘That sounds unpleasant,’ Crowley says and he suddenly realises he’s spoken aloud.

‘Everyone should have homes.’

He stands alongside Crowley in the light of the first stars and agrees.

**

Crowley’s standing on the cliffs this evening. The sky is bruised purple and red with sunset, and his coat is streaked with colours.

‘It’s cold,’ he says to Aziraphale in greeting.

‘Don’t you live in the water? How are you cold?’ Aziraphale huddles a bit tighter in his coat.

A head shake in response; something that Crowley’s picked up off of him, he thinks. Not a natural gesture but it looks right on him.

‘Not in water. We can… we can dive and swim for long periods. Especially in still water pools where the current’s easy. Not the ocean, so much. And the water’s warmer there too.’

‘Where is ‘there’?’ Aziraphale finds himself asking a moment later. Might as well burn some other beliefs, he thinks.

Crowley glances up at the sky, and Aziraphale can feel him thinking. The restless, churning tide of his ideas, of him trying to put something into terms Aziraphale would understand.

‘There are other worlds than this one. Lots of them, all interlinked in places. It’s where you get your stories and legends from, people finding the thin places, the places where they’re extra close together. My world… my world has stories of humans sometimes. And other things.’

‘We call you Water Horse,’ Aziraphale says and Crowley nods.

‘Not altogether inaccurate,’ Crowley responds after a moment. ‘I’ve seen your horses here. Similar. Weird legs.’

He can feel the amusement in Crowley’s thoughts for a moment, then the sadness that seems to be his default state; or maybe it’s Aziraphale’s sadness overwhelming him again.

‘So we…my world is sort of alongside this one. Told you, didn’t I, that whatever you’d been doing had disturbed it? You tore holes in it, great things like a star cat does when it’s hunting except you tore them in the walls between the worlds. We’ve… a lot of us were pulled through regardless. I think a lot of them were killed.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘You seem to like killing,’ Crowley notes after a while. ‘Like killing and then you don’t eat any of it. Madness.’

‘I know. And… we don’t like it, most of us. We just couldn’t make it stop, so we kept going.’ It sounds absurd like that, but hadn’t the whole thing been absurd, a frothing madman’s dream of war as glory?

‘And can you go back to your world? You said something about it, but I don’t remember.’

Crowley lowers his head. Half closes his eyes. He doesn’t look so alien now that Aziraphale’s used to him; strange and otherworldly but magical rather than misshapen, a dream or a longing made into reality.

‘I can, physically. I have been, for food and the like. For… for company,’ and he lowers his voice on that as though he’s confessing to a sin.

Aziraphale recognises shame when he hears it; is used to seeing it in his mirror of a morning anyway.

‘All living things need company,’ he recites the old lie like he’s recited all the others.

‘You don’t. You hardly come down to the village unless you’re working,’ Crowley replies.

‘How… how do you know that?’

‘Watch.’

The air shimmers for a moment. Seems to collapse in on itself. Standing where the Water Horse had been is a red haired man, eyes slightly too golden to pass for normal, long legged and lithe. He’s standing hipshot, everything about him crooked up to the lazy smile.

‘You can… I didn’t know… How?’ Aziraphale stares at him again, at the dark clothes that look too tight for comfort and the hair that looks like starfire.

‘It hurts,’ Crowley says softly. ‘Hard work. I can do it for a while, and I’m getting better at doing it for longer, but… it hurts. I can manage going around the villages, talking to people a bit. It… I don’t like being alone all the time.’

His voice sounds different like this, more as though it’s made by flesh and blood rather than thoughts alone.

‘You were in my dreams the other night, too. What else can you do?’

‘You were disturbing my dreams with your shouting, you mean. I wanted some quiet.’ Crowley runs his hands through his hair, and Aziraphale catches a slight unevenness to the movement, as though his body isn’t made quite the right way.

‘Change back,’ Aziraphale says in a hurry.

‘Why?’

‘You said this hurts. You don’t need to do it for me.’

A shrug. ‘Colours look better like this. I can see the stars. ‘S worth it for a bit, don’t worry.’

He thinks he might be worrying about Crowley for the rest of his life, and then wonders when he’d admitted that to himself. ‘Aren’t you welcome there?’

‘Asked too many questions. Tried telling them what to do too often. I … I could go back any time but most of them won’t talk to me. At least here… you talk to me. And some of the kids.’

In this form, Crowley’s hand is as soft as his coat had been.

**

He gets through the Harvest Festival in a dream or maybe it’s a nightmare. Shakes hands and gives blessings, listens to the chink of coins in the bar that evening and the slow dawning of the next day without ever making it to his bed in between.

It feels like the village is going on without him, each new day leaving him further behind. Or further out to sea, and no-one coming to see if he’s drowning.

The police come again, and so do the press. He’s not sure why; it’s not as if there’s anything new to tell them. But dead bodies are rare here and they keep asking questions until his mind stings with it; until he makes an effort to think loudly at Crowley to stay away from the beach, to keep himself hidden and safe from the searchers.

What he gets back in return is a feeling of mild disdain and then confusion. A sensation of speed, as though Crowley’s running; the countryside flashing past faster than Aziraphale can think.

And then quietness. Thoughts of being small / quiet / still and he doesn’t dare to go and visit Crowley again for several days in case he leads anyone else down there.

The cliffs are empty. The beach, inky dark by the light of a crescent moon, is empty. Flinging his thoughts out to the night gets only silence in return.

Has he dreamt it? God knows… god knows he seems to have dreamt enough of his life before the war. Dreamt and never been able to find his way back to it. Perhaps it’s not surprising that he’s made himself another dream now, to try and make it bearable.

He’d seen men do that, after all. Build walls of shimmering images around their mind so that reality couldn’t claw its way in. Armour, he’d thought, and maybe company was a type of armour as well.

In the end, he hurries home and locks the doors they’d always told him should be unlocked so the community can come in.

They come to talk to him about an Armistice service. About flowers and church bells and a bugler to wake up the ghosts. About silences, as though they know the silence before a shell hits and want to bring it here as well. About… he stops listening and nods along, mutely agreeing.

It’s mainly the old people asking, he notes. The ones who might have fought the Boers or even at Waterloo; the ones with no references and understanding of Flanders. Let them have what they want.

Aziraphale! Crowley’s voice cracks like a whip, shattering through his thoughts.

‘Aziraphale, what’s wrong?’

He glances around the table, at the four nameless individuals he can no longer quite remember, and wonders how to explain the formality of grieving to a creature born of the ocean.

‘Nothing’s wrong, Crowley.’

‘You think something is dangerous? You’re shouting it. Screaming.’

Aziraphale schools his face to stillness and tries to keep the human conversation going. Tries to hurry it along so he can stop thinking about it.

‘What do you think?’ Someone asks him and he nods without understanding, without knowing what he’s agreeing to.

He can hear hoofbeats, suddenly. Not quite right, a song slightly out of key, except that his heart recognises and soars with it.

Crowley.

‘What the hell?’ Someone else demands just as Aziraphale, in thrall to the rush of hooves, gets to his feet and turns towards the window.

The water horse is hurtling up the road as though gravity doesn’t apply to him. Longer striding than anything earthly could manage, foam that might be seawater or sweat clouding on his body, steam billowing with each racking breath.

‘Aziraphale! Aziraphale!’

It sounds like a shout for aid.

‘Excuse me, gentlemen,’ Aziraphale manages. His voice sounds surprisingly steady to his ears. He even manages to push the chair back under the table.

‘Demon!’ Someone shouts and there’s other shouts, other accusations all colliding and he’s fairly sure that he sees a flash of someone’s pistol as they run for the door as well.

He gets to it, gets outside, a fraction of a second before they all do.

There’s other people in the street; a couple of motor cars pulled up, a small group of kids looking equal parts terrified and awestruck.

Crowley, in the midst of it, heaving for breath, looks like ruin and salvation both.

Aziraphale goes to him, reaches out a hand which Crowey sniffs. It’s a surprisingly equine gesture.

‘Come away with me.’

He glances, once, at the house. At the ghosts inside it and the faceless people outside. Across the hill at the chapel with the empty lies and the stories he doesn’t believe in anymore. Across the sea although it’s the wrong direction for France.

‘It’s the thing that killed the man!’ Someone shouts, and someone else is shouting about the police. Someone wearing a cross necklace pulls it out from under their vest and waves it near Crowley’s face.

‘It’s the Devil himself!’

‘Our Father, who art in Heaven,’ and a few of them are reciting that now, glancing at Aziraphale as if they expect him to join in with them. He almost does, brain seduced by old memories.

And then Crowley asks again, voice soft and hopeful. ‘Come away with me.’

For a second, he fights it.

Crowley stares at him, yellow eyes golden in the harsh daylight. The foam’s dripping down his legs now, puddling on the ground under him.

‘Come away.’

The first step is the hardest thing he’s ever done. The second step is the easiest. A few more, until he’s at Crowley’s side and Crowley’s bending a foreleg, half kneeling down like a circus animal so Aziraphale can mount and then surging to his feet and into full gallop like the onrushing tide.

Crowley’s action is rougher than a normal horse; a spine jolting, teeth rattling horror of a thing to sit. But even as the countryside blurs around them and his hands freeze in the cold air of their rush, Aziraphale never feels threatened. Never feels that he might fall, or that there might be some misstep between hoof and earth.

‘Where are we going?’ he gasps out, crouching along Crowley’s neck. His mane’s whipping into Azirapale’s face.

‘The sea,’ and there’s a grim determination in Crowley’s voice, as though even the mental effort he needs to think his words in this form is affected by his galloping.

They’re followed; of course they are. Aziraphale knows too many old stories to doubt it; has seen too much of men at their worst to hope for anything different.

But they’re mounted on horses which tire, or in motorcars which can’t follow them up the winding path through the gorse, and Crowley runs as though he was born for this. As though he can outrun sorrow, ghosts, guns. Maybe time itself.

Aziraphale sits still and lets him run through the dying heat of the evening. Gulls, disturbed into flight, protest their passing and the sun sinks low on the horizon. He wonders what the sun might look like in Crowley’s world.

Crowley’s hoofbeats are softer now, on sand and turf rather than stone. He halts on the cliff, near to the path Aziraphale had taken the first time they met.

‘Are you sure?’

In response, Aziraphale strokes his sweat soaked shoulder. The black hair is night dark, starred with foam. ‘I’m sure.’

‘They’ll kill me if they catch me,’ Crowley says softly. ‘And they’ll kill you if you come back and they think you were helping me.’

Aziraphale takes a long, long look around them both. ‘I think the place has been killing me for a few years now, Crowley.’

In silent understanding, they pick their way down onto the sands. There’s a few people already gathered there and Aziraphale’s glad that he isn’t close enough to recognise their faces. Bad enough knowing what they believe of him now, without having it confirmed.

Crowley gatherers himself together; seems to hesitate a moment and then surges forward into the air’s embrace. Leaps high and wide across the first width of sand, so near to flying that Aziraphale thinks he’s dreaming for a moment, and then another leap, greater still. And eventually, out into the churning shallows of the waves, where he pauses again and turns his head back to look at both Aziraphale and their pursuers.

‘Stay at my place?’ and it’s said in such a human fashion that Aziraphale’s laughing. Is still laughing as the Water Horse dives forward again, landing amongst the silver waves and the first early stars, and takes them both homewards.

Willowherb Sat 31 May 2025 04:54PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Sun 01 Jun 2025 02:19PM UTC

Comment Actions

Owlharp (Guest) Sat 31 May 2025 06:00PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Sun 01 Jun 2025 02:19PM UTC

Comment Actions

alwaysburning Sun 01 Jun 2025 03:03AM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Sun 01 Jun 2025 02:18PM UTC

Comment Actions

WaitingToBeBroken Sun 01 Jun 2025 05:09AM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Mon 02 Jun 2025 07:49AM UTC

Comment Actions

lijahlover Sun 01 Jun 2025 04:37PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Mon 02 Jun 2025 07:47AM UTC

Comment Actions

Arielavader Mon 02 Jun 2025 02:43AM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Mon 02 Jun 2025 07:46AM UTC

Comment Actions

PinkPenguinParade Mon 02 Jun 2025 05:32PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Tue 03 Jun 2025 08:15AM UTC

Comment Actions

cottagecore_raccoon Mon 02 Jun 2025 06:15PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Tue 03 Jun 2025 08:14AM UTC

Comment Actions

kjerstit Mon 02 Jun 2025 10:19PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Tue 03 Jun 2025 08:15AM UTC

Comment Actions

AbAlaAvis Fri 06 Jun 2025 01:56AM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Sun 08 Jun 2025 11:11AM UTC

Comment Actions

tehren Sat 07 Jun 2025 07:34PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Sun 08 Jun 2025 10:18AM UTC

Comment Actions

Ymas Mon 09 Jun 2025 07:07AM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Mon 09 Jun 2025 09:55AM UTC

Comment Actions

Ymas Tue 10 Jun 2025 06:50PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Tue 10 Jun 2025 07:13PM UTC

Last Edited Tue 10 Jun 2025 07:14PM UTC

Comment Actions

Blue_Rivers Mon 09 Jun 2025 01:19PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Tue 10 Jun 2025 07:13PM UTC

Comment Actions

QuothTheMaiden Fri 13 Jun 2025 04:20AM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Sat 28 Jun 2025 08:36AM UTC

Comment Actions

Val_Quainton Sat 14 Jun 2025 05:12PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Sat 21 Jun 2025 12:36PM UTC

Comment Actions

Gogo_Smith Mon 16 Jun 2025 02:26AM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Mon 16 Jun 2025 08:44PM UTC

Comment Actions

Mrs_Non_Gorilla Mon 16 Jun 2025 10:49PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Tue 17 Jun 2025 04:13AM UTC

Comment Actions

Ginipig Sat 21 Jun 2025 09:40PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Sun 22 Jun 2025 09:18AM UTC

Comment Actions

glitternewt Sun 22 Jun 2025 03:15PM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Sun 22 Jun 2025 05:07PM UTC

Comment Actions

spinner_of_yarns Thu 06 Nov 2025 10:26AM UTC

Comment Actions

Snowfilly1 Fri 07 Nov 2025 08:46AM UTC

Comment Actions