Chapter 1: Wagner's Scream Chapter One

Chapter Text

Of course the Cloister Bells produce the most foreboding sound I can think of, not because they are loud or intrinsically irritating, but because of their message: “Warning! The TARDIS is in great danger!” So if you ask me what the most frightening sound is, it may just be the Cloister Bells. But if you ask me what sound was the most irritating, barely tolerable, ear-splitting, composure-shattering, possibly glass-breaking and certainly attention-getting, I’d have to say Wagner’s scream.

I am sure the one I endured was not the only scream he ever emitted, but fortunately it was the only one of his that ever reached my ears.

On March 10, 1864 the King of Bavaria, Maximilian II, died. I had known him slightly, visiting him along with my friend Hans Christian Andersen a decade earlier, staying with him at Starnberg Castle and being treated quite royally (Hans called him “King Max” and I suspect, once in a while, “Uncle Max,” although they were not related and indeed Max was a handful of years younger than Hans). Hans had a bit of a crush on me but that’s another story. At any rate I found Max charming and thought it might be a nice gesture to attend his sending-off, and at his funeral I became acquainted with his son, Ludwig, who had just ascended to the throne. Ludwig was crushing too, but not on me; the object of his devotion was the composer, Richard Wagner, of whose music I am not especially fond, but in whose sights I eventually found myself.

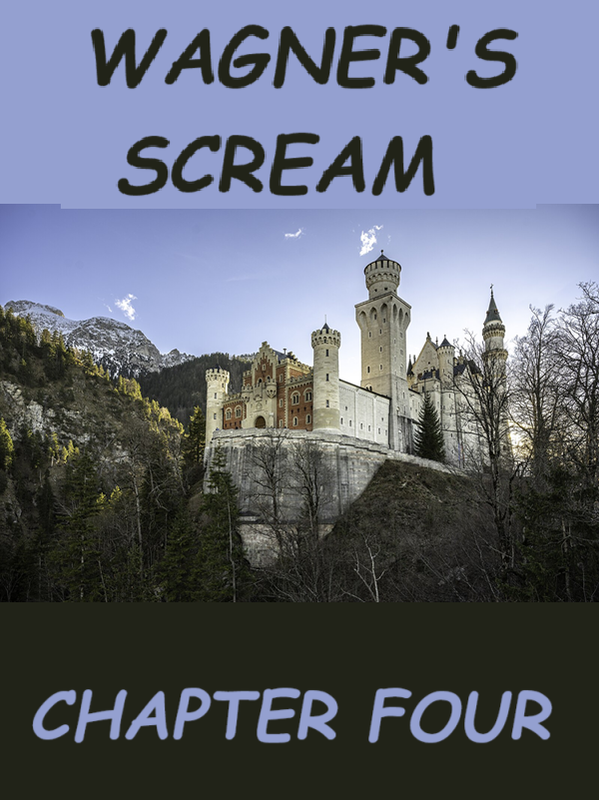

It was at the funeral that I was invited, not by Ludwig himself but by one of his friends, Prince Paul Maximilian Lamoral of Thurn and Taxis (a lovely singer, but Thurn and Taxis was a noble house, not a musical duo), to a party at Ludwig’s main castle, Schloss Neuschwanstein, two weeks later. I was looking forward to this. The King knew how to party! Although for formal events he hired professional musicians as every other nobleman did, for his really good parties he invited only trusted friends; he tended to befriend artists who then performed for him, and for each other.

I feared I had nothing to offer, and stewed about it for a short while, but then I got caught up in the excitement of the gathering, and enjoyed the tableaux, the lieder, and gave no second thought to the absence of women on the premises.

Offered my choice of beverage, I was about to ask for some lemonade, but upon learning that there was a lime tree on the grounds, I hesitated, wondering if I should try something new, and then I saw, or rather smelled, ginger brew being carried past me, and just reached for it. I know, naughty me! I don’t do this often; the TARDIS is tricky enough to navigate sober. But I wasn’t in the TARDIS. I wasn’t driving that evening, under the influence or otherwise. I drank the ginger brew and found it so delightful that I asked for, and received, and downed, another.

That’s when it struck me that that I should entertain my host with some pertinent impressions. It is a minor talent of mine. Beethoven had been gone for a few decades but my impression of him conducting his Ninth Symphony was still recognizable. My Queen Victoria had everyone in stitches. They had no idea who I was trying to portray, attempting to write Oliver Twist by acting out the parts, until I stroked my imaginary beard, and that was the clue they needed. Then I gave them my impression of a drunken cyberman lost in a maze. I am sure they had no idea who or what I was trying to be, but my antics got wilder and wilder so they laughed anyway, just to see me acting so silly, and it was quite gratifying. (I think there is a bit of a ham sandwich hidden within me somewhere.)

My performance was a smash hit but it was interrupted – pierced, actually – by that most irritating shriek: Wagner never could tolerate being ignored for long. He did not address me, didn’t even look at me, but let his glare burn everyone in the room as he declared, post-scream, that he was now going to read a book aloud from cover to cover. He didn’t add “… and woe befall anyone who dares to escape from that!” but he may as well have done. Everyone, including me, sat obediently down to listen to him read, from front to back, in its entirety, all 1,900 pages, in French, of Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables.

It was a long party.

It took Wagner more than two days to read the book aloud. He had mercy on us and read it in quarters. He took no bathroom breaks but he seemed not to notice if anyone else did. More than once, servants discreetly brought a Brotzeitplatte around, full of sausages, Kochkäse, bread, little kuchen and lots of pickles.

Well, I was in no especial hurry, and as little as I like his music, I have to say I was impressed and delighted by Wagner’s performance, and performance it was. Every wave of his hand, every twitch of his eyebrow, every vocal dynamic, was, quite frankly, thrilling. All of us, and I certainly include myself, were entranced. Those of us who stayed to the end were also exhausted, but I don’t think anyone had regrets. I know I didn’t… not yet….

Chapter 2: Wagner's Scream Chapter Two

Summary:

The Doctor receives an unexpected visitor in the dead of night.

Chapter Text

Ludwig provided his remaining guests – should I say surviving guests? – with accommodations (for as long as we needed them, I was assured, as long as we didn’t expect to hang out with the King). My TARDIS was parked discreetly some distance away, so I gladly allowed myself to be fed a lavish meal, in good company (but sans the King), then shown to my room, where I slipped on the white linen nightgown laid out on the bed, blew out my candle and went to straight to bed.

A faint sound awoke me. I lay with my eyes closed and listened for it and it was repeated, a little nearer. I opened my eyes and saw the movement of a shadow. There was no light in the room and none from outside either. How can there be a shadow? Upon the next movement I saw that the shadow’s head was disproportionately large and knew it was Wagner. He didn’t exactly tiptoe but he moved stealthily toward my bed so I closed my eyes again, just to see how bold he would prove.

The bed was sufficiently high and Wagner sufficiently short that his waist came to the edge of the mattress and he would have had to stand on tiptoe to lean over and peer at me more closely. This he did not do, although he came near enough that I fancied I felt his breath on my face. Then he turned away and I shortly heard the rustle of my coat as he picked it up from the chair where I’d left it. This I was not about to allow, so I opened my eyes, made a show of yawning and, sitting up on my elbows, feigned surprise at finding him in my room. He dropped my coat but stepped away from it quite slowly, as if I had not caught him rummaging through my pockets. He came back to the bed and stood where he had stood a moment ago, looking down at me (again) with an expression I could barely see, much less read.

“You,” he finally said, “are an alien.”

This certainly took me by surprise. I sat all the way up. “How did you know?”

“Oh….” He waved a hand in the air. Even in his attempt to be casual there was drama in the gesture. “You’ve infiltrated the musical establishment so well that pure German musicians haven’t got a chance. My friends tell me that you doctors are pulling the same stunt. How can a German compete?” He turned away and went to the fireplace I hadn’t even noticed (as there was no fire in it), and would not have noticed then had he not taken a candle from the mantle, lit it with a tinder box and put both back onto the mantle, then picked the candle back up and brought it to my bedside to light the candle I’d blown out, too. “I’ll have a better look at you, now,” said Wagner. “Yes, you look very Aryan, I admit, but you can’t tell me you’re not Jewish. I can tell, you know.” He turned away again and leaned on my bedpost. “I suppose you can’t help it. It’s in your nature and your culture. I can’t even blame you. I have nothing against you personally. Well…” and he sneaked a look back at me, “… not much, anyway. But you all will have to be stopped.”

I was not about to deny or admit to being alien or Aryan, Jewish, Roma or anything else he could come up with. (What do you do to preserve your identity while not disrespecting the identity falsely attributed to you?) Wagner’s reputation was not unknown to me but this encounter was completely unexpected. Had he come simply to vent, to ask (or command) me to leave the castle, to teach me a lesson, perhaps to murder me…? I slowly swung my legs over the edge of the bed. “What difference can it make to you what I am?”

“Come for a walk with me tomorrow.”

“I think it already is tomorrow.”

“Come for a walk and we shall talk. I want to ask your advice about something and your people are notable for their intelligence.” I may have rolled my eyes but he didn’t catch me at it. “Good night.” He abruptly left the room and I looked down, saw that my trainers were still on, took them off without unlacing them and went back to bed.

Chapter 3: Wagner's Scream Chapter Three

Summary:

The Doctor and Wagner take a physically tasking walk and Wagner asks for advice the Doctor is at a loss to give.

Chapter Text

“You are a man of the world,” said Wagner, walking slightly ahead of me as we approached the deep gorge carved out by the Pöllat River.

“Many worlds,” I murmured. He stopped just shy of the Marienbrücke, the wooden bridge high above the gorge, and turned back to peer at me.

“This bridge,” he said, “was built in honor of, and named after, Ludwig’s mother, Mary. Impressive, isn’t it?”

I looked down, more alarmed than impressed, but determined to cross the bridge if necessary. Indeed, Wagner took a step onto it, then turned back again to see if I was following. I had no choice. I stepped on as well and we crossed the Pöllat gorge.

On the other side, we began our descent into the gorge, down to the river, past waterfalls so loud that even Wagner dared not try to shout over them, so we walked without speaking, letting the rushing water speak for us. Our trek was a bit precarious; I felt pretty sure Wagner was testing my endurance, and at the same time trying to wear me down a bit, to counter any disingenuity of which he might suspect me. Exhausted people don’t lie as well as refreshed ones. I wasn’t exhausted, though, despite my sleep’s having been interrupted in such a bizarre manner. After we climbed back up the way we’d come, back to the bridge, I was somewhat winded, but unworried; despite his suspicions, I wasn’t out to trick or fool Wagner, and had no reason to be less than honest, unless you count not blurting out that he was a maniac as unforthcoming. Indeed, by the time we reached the bridge again, I hadn’t enough breath left to blurt out “Hello.” Wagner, on the other hand, had enough breath left, at least, for that, and did so, shouting into the gorge to hear himself echoed.

We crossed back, and as we approached the castle, Wagner said, “I am deeply in debt.” I must have looked as surprised as I felt, for he stopped and added, “That’s not news. I am always broke.” I had misunderstood, thinking he had said he was guilty, for the German words for debt and guilt are the same, but now I understood what he meant but not why he was telling me about it. “I am always looking for money.”

“I have no money,” I told him.

“No, I don’t mean I want money from you. Look how you dress! It is clear you have no money!” He turned to walk on and I kept up with him easily, for although he walked swiftly, my legs were much longer than his. “I know that Ludwig loves my music and wants to sponsor me.”

“Well, that’s good! That should solve your problem, shouldn’t it?”

“Yes and no. He doesn’t only love my music, you see. He loves me.” As I didn’t have an immediate response, he clarified: “He is in love with me.”

“Ah, I see.”

“No, I don’t think you do. I want his sponsorship. Don’t get me wrong, I want his friendship, too. But I do not wish to have sex with him. However, I think my having sex with him would ensure his patronage. I desperately need his patronage. As you are a man of the world, I am asking your advice. I want to be clear, though, that I am not asking you if it is wrong for men to love one another. I have no feelings about that and at any rate I don’t feel bound by such… such… such piddling restrictions, the conventions of the muddy brains of the common herd. If I loved him I would show it physically. However, I do not love him that way. I feel great affection for him, but I don’t love him the way I love Cosima. She loves me, too. We have declared our love for one another. Ah, if only she were free. And no, I don’t feel guilty if I steal her away from her husband.” He looked at me again. “I live apart from my wife. I feel free. I told you: piddling constraints are for ordinary people, not such as Cosima and me. When she leaves von Bülow we shall marry and be together forever. I am not asking for your advice or approval.” I shrugged.

“No, what I want to know, what I want your opinion about, is whether I should become Ludwig’s lover in order to ensure his patronage. Would that make me a terrible person? I do like him. He kindles my enthusiasm. I do feel affection for him. He isn’t even a bad-looking man. If a man loves his friend he should love all of him, and admire him physically as well as mentally. The Greeks knew this well enough. However, I feel no physical attraction to him whatsoever. None at all. I wish I did. That would make this so much easier.”

“I don’t know what to say….”

“Of course you don’t,” he replied, impatiently. We had stopped on the path and he now grabbed me by the shoulders. “Again, I am not asking if it is wrong for a man to love a man physically. I am asking if it is wrong to love someone physically, anyone, male or female, if one doesn’t love them altogether, and I don’t even mean exclusively, I just mean…. You know, if he was a woman I didn’t care about, I wouldn’t be asking this question, would I? I mean if she were not attractive to me. I would just do it. Any man would. These are unusual days. Surely you know we live in unusual, challenging days.”

“Yes,” I sighed. “This I do know.” I did not add that every day of my life was both unusual and challenging, and that I cherished those very qualities in my days and in my life. Perhaps I should have said something to that effect. Perhaps he had worn me down more than he’d intended and now I was useless to him. I feel now, in retrospect, that I let him down.

Chapter 4: Wagner's Scream Chapter Four

Summary:

Trying to make a polite departure from the castle, the Doctor has a further disturbing encounter with Wagner and witnesses some of the King's more unusual behavior.

Chapter Text

It isn’t precisely that I felt I had overstayed my welcome. I felt entirely too welcome; everything I could possibly want or need was ridiculously available to me. The King didn’t even know me (I was, more or less, a plus-one, and Ludwig would have been about eight years old when Hans and I had visited his father) and yet had I rung for a servant and requested a letter of introduction to Napoleon III, or a small personal harem (male or female), or a mountain of chocolate, every effort would have been made to accommodate me. I was free to wander the premises. I was bored.

No, I am not speaking quite truthfully here. For one thing, I am never bored. There is always some little thing to catch my interest, anywhere and anywhen I find myself. It’s just that too much comfort is uncomfortable for me. I don’t mind being pampered for a few minutes or even a few hours. After that, yes, I do feel compelled to seek the unusual and the challenging.

So why did I stay? Wagner’s dilemma was none of my business, but he had gone out of his way to make it my business. Our concepts of honor – I suppose that was the issue – were so far removed from one another that I really couldn’t advise him and yet I was wracking both my brain and my moral compass to find something, anything, if not useful to him then at least pithy. “Sleep with whom you like but be careful not to mislead and manipulate this teen-aged king” would have been perfect advice to anyone but Wagner (and probably unnecessary to anyone but Wagner). He didn’t need that advice. He already knew he wanted to mislead and manipulate the teen-aged king. He wanted to be reassured that sleeping with the boy to ensure his power over him would be all right.

After dinner (at which Wagner dominated the conversation, to no one’s surprise and apparently no one’s objection), I decided that I was out of my element, if not my depth, and planned to seek out the King to thank him and say goodbye, avoiding Wagner if at all possible.

It turned out not to be possible at all. Wagner came to my room again to tell me that he was going to have a wet rub-down and ask me if I would care to join him. I wasn’t entirely sure what that would involve but I was loath to ask him, and when I tried to decline, he just grabbed me by the arm and pulled me along to his destination, which turned out to be the lavish guest room in which the King had deposited him.

The furniture had all been moved to the side and had sheets and towels piled up on them, and a huge tub of water in which chunks of ice floated had been set in the center of the room. Two elderly male servants stood by as we entered the room and didn’t so much as blink when Wagner immediately tore off all of his clothing – throwing it on the floor -- and held his hands out to be helped into the tub. Both servants obliged. Shivering on a low stool in the icy water, the composer shouted, “Come on in! There is plenty of room and the ice is good for you!” Seeing me hesitate, he added, “This is my third time today!” (The weariness of the two servants, picking up his clothing, smoothing it and folding it and setting it all on the bed supported his claim.) “It is almost an obsession!”

I shook my head, backing up a few steps, lying, “I have a low tolerance for cold.” (The truth is, I can tolerate extremely low temperatures that would kill a human quite quickly.)

“I shall be quite cross, beyond cross, if you refuse to let me help you. I happen to know that your religion does not forbid you to immerse yourself as I have done, nor does your culture. In addition, I happen to know that Jews do not feel the cold as we Germans do, and your tolerance is stronger, not weaker, than ours.”

His threats to become “beyond cross” were nothing next to the effect of his ridiculous assertions on me, and, irrationally, I felt compelled to prove something, albeit not the lie I’d told. (I could not have told you then, nor can I tell you now, what I felt compelled to prove.) I removed my clothing neither quickly nor slowly, staring him defiantly in the eye, folding each item myself and handing it to one servant, then the other, alternating so that neither was unduly burdened. The tub was deep and I could see why Wagner had needed the servants’ help to get into it, but as I have mentioned, my legs were longer than his, and I was able to climb in on my own. I was only mildly surprised to find a second stool, obviously set out in advance for me. (It only occurred to me later that it needn’t have been set out for me; Wagner may have had a list!)

I sat. Wagner stared at me. I stared back at him. Then he began to sing, in his soft but emotional tenor voice, the words he had written to be sung by a bass voice, from Tristan und Isolde:

“Where now is loyalty

if Tristan has betrayed me?

Where are honor

and true breeding

If Tristan, the defender

of all honor, has lost them?”

He stopped there, although the verse was far from over. Since he had taken the role of King Marke, I replied, in my tenor, as Tristan:

“O king, that

I cannot tell you,

and what you ask

you can never hope to know.”

He seemed pleased that I knew his aria so well, but annoyed by the exact lyrics I had chosen. He stood up and allowed himself to be helped out of the tub, and then the servants each offered me a hand as well. With their aid I climbed out of the tub and stood rather uncertainly by it. Each servant took a sheet and soaked it in the cold water, and then one of them wrapped Wagner from chin to ankle in his sheet, and the other, before I could stop him, wrapped me likewise in mine. The stools were extracted from the tub and we sat on them, shivering at least as much as we had when immersed.

We neither conversed nor sang.

After a short while our sheets were politely taken from us and I was left standing naked by the tub as Wagner went to the high single bed, much like the one I’d been assigned, and, carelessly pushing aside his clothing (and mine, which had been laid out there too) lay face-down on it, crosswise, so that there actually would have been room for me to join him with a few feet between us, had he not chosen the center across which to sprawl. I sat back down on my stool.

The servant who had wrapped and unwrapped Wagner now produced some strips of cloth, dipped them in the tub and at last performed the promised wet rubdown, for which, halfway through, Wagner rolled over onto his back.

I grabbed a towel from a chair that had been pushed against a dresser, dried myself rather quickly and less than thoroughly, recovered my clothing from the bed without interfering with the rubdown and recovered myself, located my trainers by the door and slipped them on, and left the room, more determined than ever to find the King, thank him for his hospitality and leave Schloss Neuschwanstein.

Had I not got myself a little lost I’d have run into some servants, who likely would have informed me that the King was dining alone and did not wish to be disturbed. Since I did get myself at least a little lost, maybe more than a little, I found myself at the entrance to the dining hall and opened the door a crack, to see if I was in the right place, and through the open door I saw the King discoursing animatedly, sometimes waiting alertly for a response, sometimes laughing or frowning or otherwise reacting to a response (which I was unable to hear), and at any rate not dining alone at all. I slowly, silently opened the door a bit wider, to see that the long dining table was set for six besides the King, and he was still apparently conversing with his six guests, but no one was seated at the table, nor indeed was there anyone but the King in the room. I quietly closed the door and wandered back the way I had come, or so I hoped, since I was, after all, still much, much more than a little lost.

Chapter 5: Wagner's Scream Chapter Five

Summary:

The Doctor gets himself lost and then into a bit of trouble involving a false accusation.

Chapter Text

I had no good excuse to be lost; there were only 15 finished rooms in the castle. The other 185 were in various stages of construction (or even just planning) and if I encountered them I could readily see I was in the wrong place. I was pretty sure I had started out on the fourth (top) floor, and had I gone down to the ground level I’d have found the kitchen and been able to ask for directions. That didn’t happen. I’m not sure exactly how far down I went, or even why I went downstairs to begin with, since my assigned room was on the fourth. Nonetheless, I found myself wandering through what I felt sure were the King’s private chambers and went looking for a way back out. I wasn’t worried about finding my room; I had left nothing of my own behind. An exit to the castle grounds would suit me fine; all I’d have to do would be to orient myself enough to locate the TARDIS. No one was about. There was no one to ask. I found my way back into a hall, took a moment to catch my breath and then spotted a trio of Life Guards in short blue jackets with brilliant red collars and cuffs, and tall caps topped with bearskin. I was rather delighted to see them and well amused by those caps, and quickly approached them, but slowed down when I saw that they were fast approaching me as well. It was too late to run. Two of them grabbed me by the arms and threw me against the nearest wall.

“You are the Doctor?” barked the third guard, who had not touched me.

“Yes, I am. I was looking for the….”

“You will come with us.”

“Yes, I believe I shall.”

“There were witnesses,” said the King, patiently. “You were seen.”

I was trying to be patient too. “Since I don’t know yet what it is I’m supposed to have done, there is no use in denying whatever it is. I am pretty sure I have done nothing that warrants the treatment I have received, but if I have inadvertently transgressed….”

“Don’t play coy with me. You were seen and I have Herr Wagner’s word as well that you attempted to… attempted to….” The King put the palm of one hand to his forehead as if what he was trying to say caused him physical pain. Then he lowered his hand and said, to the floor, “You attempted to have intimate relations with Herr Wagner. Unwanted, uninvited intimate relations.”

“I assure you, Your Majesty….”

“Your assurances are meaningless. Wagner would not lie to me and as I say there were witnesses.”

“I cannot be witnessed doing what I never did.”

“I want you to know,” said the King, still not looking at me, “that I do not buy into this fantasy of Herr Wagner’s, that your people…”

“My people!”

“... are responsible for all the ill in the German Empire. That you are all corrupt. I cannot nor shall I ever believe such a thing. It makes no sense. He is a wonderful person, to be sure, and his music is divine. I forgive him this one little error.”

“If only you knew,” I muttered.

“I am young but I am not stupid. He has a certain magnetism. He attracts wrong types as well as those truly interested in art and music. Even the way he stands, the way he comports himself. He….” He stopped himself. “My point is that it is easy for him to fall in with the wrong crowd even though the right crowd is so drawn to him, you’d think they would offer some protection. Well, I intend to offer a great deal of protection, from the corrupt and those who would corrupt others. But to think that you would lay hands, even a finger, on the person of such a… person!”

“If I may be permitted to speak, Your Majesty….”

“This is not the time,” said Ludwig, sharply. “With Austria nipping at my heels and Prussia prodding me… They think I’m a little boy!” He snorted. “I need to deal with Bismarck, not you. You can stand with your foot in your stomach.”

“I suppose that means the dungeon for me,” I called out as my arms were once more gripped and I was dragged out of the throne room.

“We have no dungeon,” one of the guards informed me. “You can twiddle your thumbs in your room. We’ll wait outside in case you need anything.” His snicker at his own joke told me I’d better not need anything.

House arrest is not the worst fate that can befall a prisoner. Three days they held me, but they also fed me lavishly (no bread and water regime), offered me no corporal punishment (although the verbal abuse was unrepeatable) and left me largely to my own devices. I had in one of my pockets a deck of Bicycle playing cards and only in retrospect realize, now, how lucky I was no one took any interest in that deck, since I was, in a sense, introducing it 11 years prematurely. I’d invented a form of solitaire, not a terribly challenging one (but solitaire exists solely to pass the time, doesn’t it?) that involved matching cards from each end of the deck. It didn’t engage me for terribly long periods of time, but it helped. I sang a good deal, both to amuse and comfort myself and to annoy my guards, in all of which endeavors I succeeded, possibly because I sang every bit of Wagner I could remember. Since I dislike his music, I was and still am amazed that I could remember any of it as well as I did.

The trouble is, I couldn’t remember the order in which he wrote his operas. I may well have warbled some arias he hadn’t yet written.

“Through forest and meadow, heath and grove,

chased me storm and strong distress:

I do not know the way I came….”

Prince Paul Maximilian Lamoral of Thurn and Taxis had gone home before the reading (at the party to which he had invited me – I was, if you recall, his plus-one) was over but, hearing I’d been accused, and of what, he came to visit me on the second day of my house arrest. The guards let him into my room, where I was sprawled on my stomach on the floor, playing solitaire, wishing I’d asked for some books to be brought to me. At first I thought that my visitor had done so and then I recognized him. He was standing over me, shaking his head.

“I never thought that of you,” he said.

“You still shouldn’t. It isn’t true.”

“They say there are witnesses.”

“Witnesses can be bought, or coerced. Do you really think I would assault anyone, male or female, sexually or otherwise?”

“I don’t know you all that well. I shouldn’t have thought so. Yes, I know, that’s what you said: I shouldn’t.”

“Well, it’s not true, and I suspect either it will come out that someone is lying – and it won’t be me – or I shall be successfully framed and punished, hopefully not in any permanent manner.”

“Such as death.”

“...or transfiguration,” I couldn’t resist saying, but as Richard Strauss was a couple of months shy of having yet been born, Paul only frowned.

“Banishment, at the very least,” he finally said.

“That would suit me fine.” I put away the cards before he could notice their design, and sat up. “Has anyone said how long I am to languish here, and if more than another hour, do you think you could convince them to bring me some books? Any books. Any language. I’m a quick study. Even Tibetan would be fine.”

Paul laughed. “I’ll see what I can do.”

No one brought me a book of any sort, in any language, and I languished for yet another day and a half.

Chapter 6: Wagner's Scream Chapter Six

Summary:

Still under house arrest, the Doctor receives another unusual wee-hours visit.

Chapter Text

At the end of the third day and halfway into the night I was lying in bed, asleep, fully dressed in case an escape opportunity should present itself, when instead, Wagner presented himself. I don’t know why he was allowed in; I suppose what we are used to as normal rules of jurisprudence don’t always apply in kingdoms, especially those rules as understood, or misunderstood, or just missed, by neophytes, not that his being young or even his already being in charge were at all Ludwig’s fault. (Somehow I think being admitted to my room in the dead of night was clearly enough outside the scope of what was or was not normally allowed that there had to be a bribe or a favor involved.) However it happened, Wagner was permitted to enter my room in the middle of the night, and once more he stood by my bedside contemplating my slumbering form. This time I really was asleep, but his gaze awoke me, or perhaps it was his steady, even breathing. Again I kept my eyes closed and feigned continued sleep.

As my coat was on me instead of on a chair, Wagner could not repeat his efforts to examine my pockets, so instead, once he was done watching me pretend to sleep, he sat on the chair and did nothing as far as I could tell, for although I still kept my eyes closed, I would have been able to hear any movements he made. Maybe if my act was sufficiently convincing and I was incredibly lucky he would give up and go away. I am sure he was not there to do anything to me physically; his icy little performance had been a set-up, and if he’d meant to harm me, he could have smacked me with the fire poker, smothered me with a pillow or even just beaten me with his fists. Instead he sat still in the chair; perhaps he eventually fell asleep. I didn’t. I lay awake, afraid to move a muscle. I did not want Wagner to speak to me and I didn’t want to speak to him.

I had thought finding out why he’d lied about me would be the proper thing to do; I’d imagined him coming to taunt me and my somehow getting him to confess he’d lied and somehow got the servants to lie as well. I thought I’d care about his answer, and maybe help him resolve whatever was plaguing him that made him do such a thing, and forgive him for getting me into trouble, and be forgiven by him for stealing his thunder at the party, or not being able to advise him, or not letting him practice on me what he had planned for Ludwig, or whatever it was he thought I’d done that had earned me a frame and whatever was to come. Now that he was here, I surprised myself: I didn’t care. I just wanted out.

Then I felt guilty for not caring. I knew I couldn’t change anything major in Earth’s history. Imagine if that could be done: chaos! The butterfly effect would be enormous. I knew what would become of Wagner and, alas, what would become of the King. (But if I prevented Ludwig from drowning, or more probably being drowned, Earth’s human population, itself not without huge effect on the rest of the planet, could simply, collectively hiccup, or history could be changed in unthinkable ways.)

But on a minute-to-minute basis, couldn’t I find a way to ease Wagner’s mind – not regarding how he planned to influence the young King but regarding what I still think of as his borderline personality disorder. There are therapies for that now but the disorder would not be named until a third of the way into the next century and it wouldn’t become an official diagnosis for more than 100 years. I am the Doctor but I’m not a Doctor, of psychology or anything else. What could I do for Wagner? Could I find a way to make him less desperately adversarial in how he saw himself in relation to the world? Isn’t that what we all want: an easier way to see ourselves in relation to the world? While I was at it, couldn’t I find a way to exit 1864 Bavaria without feeling I’d left behind lingering misunderstandings, enemies and, if I was very unlucky, a legend?

When day broke, Wagner tore the drapes open and sunlight spilled into the room. I may actually have drifted off by then. Wagner clapped his hands loudly and yelled: “Rise and shine!” Reluctantly, I sat up in bed and stared blearily at the composer.

There was no further need for pretense. “Why did you sit in that chair all night and watch me sleep?” I demanded. I was speculating about his watching me; for all I knew, he’d slept in that chair.

“I didn’t want to wake you.”

“Can you close those drapes? The sun is right in my eyes! Why did you have to open them all the way?”

“I wanted to wake you! I have something to say to you.”

“Yes, I figured you would.”

“When I was a child, I was often ill. You know my mother died a few years ago?”

I hadn’t known offhand. “Yes. I was sorry to hear of it.”

“She told me before she died that when I was ill, which as I say was often, she almost wished I would die.” I studied my feet. “Almost, mind you. Still.”

I looked up at him. He had moved himself to tears. I believed him but at the same time I knew that he had moved himself to tears on purpose. “You conspired to ruin my reputation and maybe even cause me other harm. It wasn’t even a spontaneous act, much less a misunderstanding. You set me up.”

“I never said a word to Ludwig. Not one word. Today I will explain to him that it was all a misunderstanding and that you are innocent and should be set free.”

“Thank you very much, but you owe me an explanation in addition to exoneration. An apology wouldn’t hurt my feelings either.”

“You have balls, I’ll hand you that. Asking for an apology!”

“I am owed.”

“All right, all right, I wanted to make Ludwig jealous and it all went wrong so I got mad.”

“At me.”

“Well, who else?”

“Richard – I assume by now I may call you Richard – do you ever care what someone else thinks or feels except insofar as it affects you? How they feel about you? What they think about you?”

“No, of course not.” Wagner was genuinely puzzled. “Whyever should I?”

Chapter 7: Wagner's Scream Chapter Seven

Summary:

The Doctor is exonerated, leave the castle, has one more encounter with Wagner, and recounts his story to his friends.

Chapter Text

“Richard has explained it all to me,” said the King, “and I am sorry you were the butt of his little joke, but no harm done, I hope.” I was silent. “Brilliant men have the right to be a little… eccentric, don’t you think?”

“Of course, Your Majesty.”

“You may stay if you like. Richard is properly penitent and should bother you no further.”

“Your Majesty, forgive me, but I am needed elsewhere, and will burden you with my presence no further.”

“Will you come to my coronation this autumn? Perhaps the ceremony will bestow upon me some wisdom I currently lack.”

“I wish I could,” I lied, “but I will still be needed elsewhere at that time. But Your Majesty?” He seemed surprised to be further addressed with more than a “thanks” or a “farewell,” and raised a royal eyebrow. “Be careful, Your Majesty.” He looked relieved. I thought he shouldn’t have, but I knew better than to go on. I bowed and made my exit, accompanied much more respectfully than I had been before, onto the castle grounds… where I found Wagner waiting for me.

“You have impressed me with your courage,” he said, walking with me in the general direction of my TARDIS, which was the better part of a morning’s walk away. I wanted to shake him off before he could get so much as a glimpse of it.

“I have done nothing courageous,” I said, truthfully. Courage would have involved giving Wagner a thorough dressing down. Well, it wasn’t actually lack of courage that held me back; it was, once more, the potential impact on Earth’s history. (But maybe the impact would have improved Earth’s history....)

“I shall write you into an opera one day,” he promised, “as the hero. The naive hero, how about that? A knight, perhaps. That will be my formal apology to you. I shall have to think long and hard about how to accomplish that. Where do you fit into my operatic vision? My world?”

“It’s not necessary.”

“I don’t think it’s your place to tell me what I do or do not need!” he shouted. Zero to sixty, I thought. The man has no filter whatsoever. Then he smiled, as if he hadn’t shouted at all. “I know you want to heal me. I cannot be healed. It’s all right. I was born to suffer.”

To my relief, he turned on his heel and was gone.

I caught up with Tegan and Turlough at Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart’s cottage in 1986, in time for tea. “How was the funeral?” asked Tegan, not at all surprised that I turned up three minutes after I’d left.

“The funeral was uneventful,” I said, truthfully. “After the funeral, things got weird.” I recounted my little adventure rather incompletely but they got the gist, and immediately demanded a repeat performance of the drunken-cyberman-in-maze act. I obliged.

“Did he ever stick you in an opera?”

“I don’t know, Tegan. I’ve never listened to a whole one; his music is a bit, well, screamy, for me, if you want to know the truth.”

“I know what you mean,” said Turlough. “I don’t know why the sopranos always have to scream out his songs. Do you think he intended that?”

“Maybe. We’ll never know.” I thought for a moment. “I did hear a lovely rendition of one of his arias that wasn’t screamy at all. Elisabeth Rethberg. She is the only soprano I can think of who never screamed her Wagner, not even on the highest notes. She almost made me like Wagner, or at least his music. I wonder if he would have approved of her?”

The Brigadier, who had been silent throughout, spoke up now: “You know, I know nothing of opera, nothing about Wagner but what you have just told us, but the man sounds absolutely insane. Why did you put up with his behavior? Why did anyone?”

“Well,” I mused, “King Ludwig said that brilliant men had a right to be a little eccentric.”

For the life of me I can’t understand why the three of them laughed so hard at that.

THE END

butterflyrooms on Chapter 2 Wed 02 Jul 2025 06:07AM UTC

Comment Actions