Chapter Text

The third step always creaks. Announces one's arrival louder than any footman could, Penelope reckons. She has made a game of it these past few months — seeing how little racket she can make or how lightly she can step. Like a bird alighting on a branch just to flit off it again, leaves rustling in its wake.

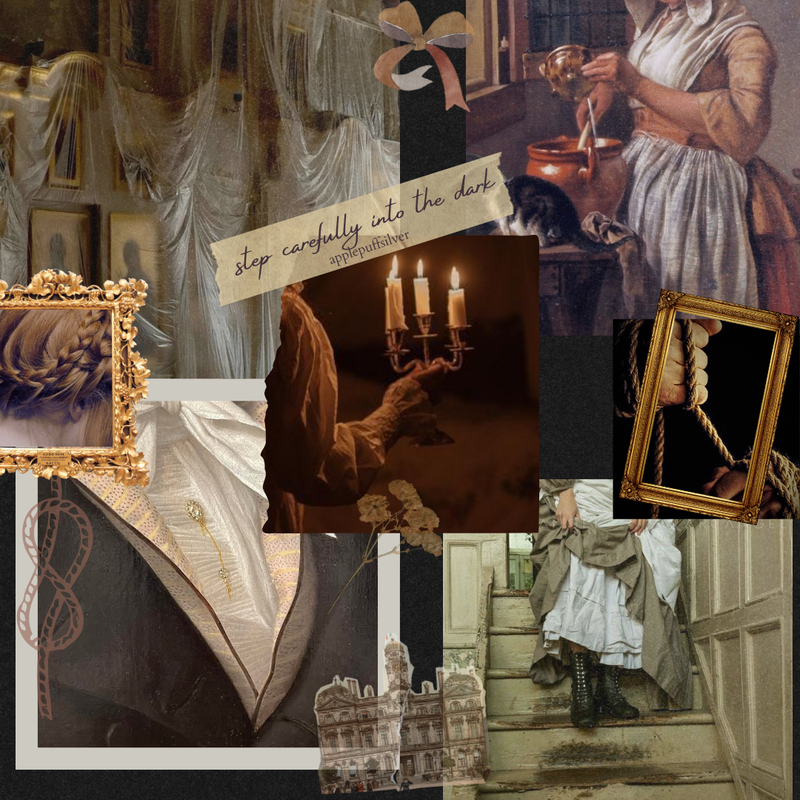

Tonight she skips it altogether, though it is rather difficult with her short legs. She teeters a little, thrown off balance by the candle-holder she grips. The flame wobbles, throwing large, stretched shadows up the staircase. Unsettling shapes: dark ghosts that seem to chase her up the stairs. She catches her breath, careful not to blow out the shivering flame — she does not relish the prospect of making this journey in the dark.

Servants' stairs are never the prettiest, of course, but the ones in the house on Bloomsbury Square are especially grim. Whole house is a bit grim, if she is honest (even with Penelope's best efforts to clean up). But Penelope really does not like these stairs, so another game she likes to play is to see if she can make it all the way up the winding stone stairs without taking a breath; so that if some malevolent spirit is waiting for her, she thinks, it might mistake her for one of the dead and might thusly leave her alone.

She knows her Ma would call her silly for such fancies (she is eighteen, after all) but a girl has to entertain herself somehow.

The real silliness is why she does not just use the other staircase. It is only her and the master, and he hardly comes out of his room except for mealtimes. She might promenade up the main staircase naked with the breakfast tray balanced on her head singing "La Marseillaise" and not a soul would see her (she smiles to herself at the image as she resumes her flit up the stairs). But she cannot make herself — the only time she sets foot upon the grand staircase is to clean it.

She cannot. It is not her place. She wonders if perhaps there is some weakness in her spirit — some inherent servility woven into her bones that makes her unable to misbehave, even when there is no chance of punishment. Or perhaps it is, instead, due to the feeling she cannot shake; the feeling, ever-present, that there are ghosts in this house. Ghosts pitched up in the ceilings; ghosts layered over the moulding in some shadowy veil. Bare, socketed eyes watch her as she cooks and cleans and sets the fire. They flatten and swell and fold themselves into every nook, settling like dust upon the furniture no matter how many times she sweeps.

They are not malevolent — not precisely. But she feels them, and they are everywhere, and they witness everything. She stirs them into her tea and shakes them out of the laundry. Sometimes she wakes up in her cold attic bed and feels that they have crawled beneath the blankets with her, cuddled up for warmth. There is no escaping them, or their eyes, and she gets the sense they would not approve of her swanning up the staircase as if she were the lady of the house. That one died.

Penelope bursts into the upper hallway and takes a chilly gasp of air. It is better lit up here; the lamps water pale light from their sconces, but she clutches her candle nonetheless. The brass warms beneath her fingertips, and it soothes her.

Here is the master's door. She knocks upon it, as she does every evening before bed. Mr. Bridgerton does not have a valet, so Penelope must suffer the indignity of those tasks as well: hanging up his discarded clothes; taking away those to be mended; cleaning up his washbasin (and his supper things, if he has taken his dinner in his room). Penelope is maid and charwoman and valet and house-keeper and cook all at once, and it should be too much for one lass except the master does not demand much. He does not complain about the simple fare she serves him and he only keeps to two rooms, his chamber and the library. The other rooms are locked up tight, with sheets over the furniture. Penelope is sure they are brimming with ghosts, and so she has not hazarded a peek inside any of them — though she is a curious girl by nature.

Furthermore, he pays her handsomely. Enough that Penelope can withstand the impropriety of having to hold the mirror for him while he shaves in nothing more than his shirt-sleeves, leaving his long, pale throat bare.

"Good evening, sir," Penelope calls out as she pushes open the heavy door. She keeps her gaze down, glancing around beneath her lashes for his kicked-off breeches and soiled shirt. Stooping to pick up his vest, which he seems to have shucked off by the door.

"Ah — Penelope —"

Her eyes are tugged up by the ragged burr of his voice — for he so rarely speaks to her, and almost never her name.

Her gaze moves like a spoon through treacle, slow and unwieldy through the dim room. There is the Ottoman rug, red and gold spirals set in deep green (one of many such exotic and mysterious curiosities in this house that she dare not ask about). There is the mahogany bedframe, sturdy and familiar. There, the white crumple of the bedsheets, pulled back carelessly after Penelope spent so long righting them this morning (as every morning).

And there, her master. Propped upon his pillows in his nightshirt, the fluttering orange of the candle spilling shadows over his body. One leg tucked up, the other stretched out straight. A nice sort of leg, Penelope thinks, swallowing at the sight of the muscled calf and thigh covered in thick dark hair, and there is something— surely not —

Can it be rope? Hessian braids of it, tangled all the way up his leg in oddly uniform knots. Twisted into repeating diamonds, like the geometric shapes that decorate the border of the rug.

Penelope takes half a step closer on instinct, her hand reaching forward into the candlelit air and her mouth sagging open.

"Oh — sir — you are caught, allow me to —"

She is sure she hears the ghosts laugh. Because he is not caught or tangled; he did not haplessly stumble into this webbed trap like a fish scooped up in a net. His large, veined hands hold onto the rope ends firmly, and as she steps closer she sees the purpose behind the design encasing his leg. Her master, she realises, has tied himself up.

Mr. Bridgerton is a strange man.

Or — that is what other people say. The butcher and the grocer and the man who brings the wood for the fire. Strange sort of fellow, they say, lingering upon the threshold. They lean against frame of the kitchen door while their eyes trail listlessly from Penelope's bosom to the space above her head, as if they expect to see Mr. Bridgerton skulking, bat-like, in the shadows behind her. Are you sure you are safe? they say, forever leaning, leaning, as if they might lean all the way down and put their faces directly to her breast. A little thing like you and that strange fellow all alone in here. You ought to be careful.

I am not afraid, Penelope tells the leaning, lingering men, gathering herself up indignantly to meet their hollow gazes (more malevolent than the ghosts, she reckons).

Penelope does not think he is strange. She thinks, rather, that he is sad.

And yes, well, she supposes he is not quite like other gentlemen: he does not take visitors and he does not leave the house and he does not speak much. In truth, in these past three months working at the house on Bloomsbury Square, Penelope has not spoken with him beyond enquiring if he would like salt and pepper with his supper and which shirt he would like her to press. But he is always polite to her, and last month when she accidentally spilled the ashes from the grate across the rug in the library he did not get cross or shout (like other masters might).

Mr. Bridgerton's wife died five years ago, and Penelope thinks he still carries the grief around with him. As though there are shackles upon his ankles, weighted irons he drags about the house in his shuffling way. Perhaps that is why he sticks only to those two rooms, for the chains would be far too heavy to carry down to the parlour (let alone outside the house). So she feels oddly… protective of him, placing herself like a barrier at the kitchen door. A wall that the mean eyes of the grocery boy and the wood-man cannot pass through. Another silliness, for he is forty and a rich gentleman and has abdicated, in his hermitage, more power than Penelope will ever hold in her life — but she supposes she is a girl still, and prone to silliness, and she must keep herself entertained.

He looks at her now with eyes dipped black in the flickering light, like the eyes of a hunted animal. A handsome man, Penelope thinks to herself. She always thinks this when she looks upon him, though he is grey at the temples and there are blue hollows smeared permanently beneath his eyes (are those tear-tracks upon his cheeks, or is it a trick of the light?). His night shirt is open at the collar and she sees dark curls peeking out, coarse and unkempt, and the hair upon his head sticks out wildly. It is unsettling seeing him so unravelled, as even in his grief he is always rather neat and composed. Chatelaine at his belt with a little watch-face upon it that he checks compulsively. Cravat tied though there is no-one in the house but her and the ghosts. Perhaps he, like her, feels their eyes upon him. Feels their shadowy gaze demanding propriety.

The rest of the house was a mess when she first arrived here, but never him. Never him.

Penelope watches the ghosts' dark fingers caress Mr. Bridgerton's body through the shadows cast by the candle. She should not be looking at his body, she realises — not the hair upon his chest nor the bare leg, nightshirt hitched to his thigh, rope entwined —

She drops her gaze to the rug and counts the flowers that wind around the border. "Forgive me, sir," she murmurs rather breathlessly, as if she has just escaped the servants' stairs without a single sip of air.

"No — please — it is I who — I am sorry —" Mr Bridgerton stutters uncomfortably. Then he catches himself and takes a deep inhale. "I shall explain."

Penelope's cheeks burn for reasons she cannot fathom. For though it is, of course, unusual that a man would bind his leg so, there is no reason for it to feel so… intimate. As though she has intruded upon something that she was not supposed to see. Sheets rumpled and hair mussed, as if by some phantom fingers. As though she has caught her master and the ghosts in an embrace.

"There is no need, sir," she mumbles, her tongue thick and her legs wobbling as she curtsies. "I shall take my leave."

"Please stay."

He says it firmly and simply, and Penelope cannot disobey, though she wishes very dearly to flee all this strangeness. She nods and bows her head and keeps her eyes firmly upon the rug so they are not tempted to creep over all the bare skin drenched in shadow and flame alike.

"The rope is something I was taught," Mr. Bridgerton says stiffly. Haltingly. "By an Italian sailor who had learned it in the East. I practice it when I feel… overcome." He says the word delicately, as if he handles some fragile glass. "It helps focus the mind when all else feels a tangle. Do you understand me, Penelope?"

"Yes, sir," she answers, though she is not quite sure that she is not lying. She feels curiosity burn like a flaming seed in her belly, fiery vines sprouting and winding through her limbs. She bites her tongue to stop herself from asking all the questions that she wishes to: Where did you meet an Italian sailor and Did you have the rope made specially and Is this what you do all day in the library?

"Good girl." Penelope feels something ragged and spiked in her chest, like a bramble has lodged itself inside of her. Her breath snags in her throat and she grips the brass handle of the candle-holder tight. The metal has grown too warm, her hand sweating. "It helps calm me, though the effects of tying up oneself are not quite as fruitful as tying another. I have tried it upon the bedpost but it is not the same." His words come out in a rather desolate sigh, and he wipes the back of his hand over his face.

That burning seed bursts into life upon her tongue, and she cannot keep it in a moment longer.

"You — you bind other people?" Penelope blurts out, forgetting herself. Then her cheeks redden. "Sir," she adds, her heart pounding.

Mr Bridgerton's brow creases and he looks down at his leg, at the rope wound about his large fingers.

"Yes, Penelope. The feeling is like none other. I am able to… well." He clears his throat and his back straightens. He has never said so many words to her all at once, Penelope realises. "The rope allows one to forget one's troubles for a few moments."

Penelope does not think before she says:

"I am yours to command, sir."

Penelope wishes to suck the words back into her mouth the moment they drop from her tongue; longs to bite the air and chew them back down. She feels the ghosts plastered to the ceiling above her head, large eyes pressing upon her plaited crown in silent judgement.

I know, I know, she tells them. I do not understand it either.

Except — well — it seems like a small thing to let her master wrap some rope about her body, does it not? And if it will help him shake off his grief for a few moments, then… why should she not offer? He is sad and kind and he does not ask much for all that he pays her. Why should she not?

(Because he will have to touch you, the ghosts answer. Because he will put his hands upon you, perhaps peel off your stockings so he can run his fingers over your thighs, the backs of your calves, trace circles over your ankles —)

Mr. Bridgerton seems just as astonished as she is.

"Oh — Penelope…" Her name sits warily on his tongue. "You — you cannot mean it."

She should agree, and bow her head, and run away with her flittering candle, just as the ghosts wish her to.

"Must it be — must it be the leg, sir?" she asks instead. She feels as if she is creeping through an unfamiliar room in a blindfold, hands outstretched in the darkness.

Her master sits up straighter and she sees a keen cautiousness upon his face.

"No. I could — I could tie your arm. Or a foot. Nothing — nothing improper. If — if you wish it." He peers at her, some desperate hope in his voice. "Do you mean it?"

"I — yes, sir."

Is he trembling, or is it just the shake of the candle in Penelope's hand? It spills a shuddering light over the bed as she forges ahead blindly, another step into unknown darkness.

"Come here."

Again the bramble snags at her at the soft command in his voice.

"Now, sir?" she asks tremulously.

He tilts his head to one side, unsure.

"Yes, if you — if you are willing —"

"Yes, sir."

Her feet make no noise as she steps across the rug — or perhaps the clanging in her ears is too loud for her to hear it. Mr. Bridgerton's hands work quickly to tug the rope from his leg with deft, practiced movements. He pushes his night-shirt down and sits up straight as Penelope approaches.

She stands a foot from his bed, swaying uncertainly upon the balls of her feet. Mr Bridgerton pats the rumpled sheets near his feet.

"Please. Sit."

Penelope hovers for a moment, the ghosts rushing in her ears. Then, she places her candle upon the side table and sits carefully upon her master's bed. She has to hop a little, for it is very tall, and her little legs dangle. The ghosts wail and crow — this bed is for the lady of the house, not for her — but she ignores them, and asks her master What is next? in a voice that only trembles a bit. Hardly at all, really.

"Hold out your arm," he commands in that quiet, firm manner. "And close your eyes. It is better if you are relaxed."

Little burr, spiked and wicked. She holds out her arm and, with a deep breath, closes her eyes. Her eyelids shutter slowly, the orange candle flame still flickering against the thin skin — but somehow, the light feels nicer like this. Like walking under the trees in the park in the afternoon sunlight, dappled and gentle.

She tries not to flinch when he takes her hand. Grips her wrist over the thick blue brocade of her uniform. Draws her arm to him. Not because she is afraid of him — it is only that this is all so strange, and he has never touched her before (except once, when she almost tripped on her skirts with the tea tray and he caught her by the elbows; righted her).

"You must tell me if anything pinches, or if you start to feel numbness in your fingers," he says, tapping her index finger as if to remind her where it is. "And keep your eyes closed."

Penelope nods, "Yes, sir." Barely more than a whisper, barely louder than the sheets that she shifts against.

"Good girl."

Penelope swallows.

It is strangely… peaceful. He moves slowly but purposefully, his touch crossing back and forth over her forearm. The rope is thin, hardly thicker than her pinky finger. A little rough, too; it prickles through the fabric of her dress. Penelope feels as if she has slipped into the entire bramble bush somehow, the spines catching her clothes and hair and skin so she cannot move in any direction. It is no use — instead she sinks into it. She melts into stillness as her master ties up her arm.

She longs to open her eyes, to peek at him (for she is a curious girl, no denying, and she can hear him breathing long and slow like the ocean and she would like very much to see his face as he does so); she considers the nice warm voice he used when he called her good and she wishes very dearly to hear it again. So she does not; instead she is still and quiet as she sinks into her brambles, dappled sunlight in her eyes; after a moment she begins to feel as if she could lie back upon the bed, though she knows it would be most improper.

"How do you feel, Penelope?"

His voice seems to come to her from very far away. As if he is speaking to her from the other side of a large field and the wind has picked up his words and delivered them to her, gusty and faint.

Penelope swallows and attempts to gather herself — though the fingers that trail upon her arm, slotting beneath the rope as if to check the tension, are very distracting. Thorns in her clothes.

"Um," she murmurs. "Calm, sir. Very calm."

"Excellent," Mr. Bridgerton says. Penelope feels the snag, her breath jagged in her lungs. "Not everyone finds it so."

He pauses, his thumb easing back and forth over her exposed pulse on the inside of her wrist, where the skin is thin and laced blue. Penelope wonders if he can feel the slow, heavy thump of her heart beating alongside his every ocean-breath, as if his lungs command her blood like the moon the tides. She has the strangest urge to lean into him, to rest her head upon his shoulder and let herself drift into nothingness while he touches her so, so gently, like eyelashes fluttering upon her cheek.

"Th-thank you, Penelope."

His voice is thick and sincere and a little rough around the edges.

"Oh," she says, for she has little idea what else to say, her mind having drifted rather far away from her body. She feels somewhat embarrassed by his thanks, though that feeling comes from far away too. "Sir."

Mr. Bridgerton clears his throat.

"I shall untie you now."

"Oh," Penelope repeats, for she has become quite senseless in her calm. She would like to ask him to leave her tied for a moment longer (so she might revel in her brambles and sunlight for a heartbeat more), but she cannot imagine how she would phrase such a thing.

In any case, the untying is just as pleasant as the tying. Penelope sways a little in his hold, her mind spooling over the crisp sheets she knows so well — sheets she has scrubbed and rinsed and hung out and pressed; tucked in at the corners and smoothed over with the hot-iron to make sure the turn is sharp and pristine — sheets she is not allowed to sleep upon. How nice it would be to crawl into their softness, lay her head upon her master's pillow and sleep!

"You may open your eyes now."

Heavily they blink open, the spill of the candle flame bending and smearing in a bright streak in her vision. Mr. Bridgerton still cups her fingers carefully in his hand; slowly he places her hand in her lap, as though he is returning her arm to her after borrowing it for a short time. Her entire limb feels buzzing, the memory of the rope weaving across her skin. Penelope rubs her other hand back and forth across the brocade of her sleeve, hazy and uncertain. She longs for her bed but she feels strangely loath to leave this room.

Penelope feels her master's gaze upon her. Expectant and waiting, though she does not know what for.

"Do- do you need anything else, sir?" she asks eventually. Her tongue moves of its own accord, for is it not what she asks him every night?

Mr. Bridgerton pauses, his eyes dark and shaded.

"No, Penelope."

"I shall let you rest, then." She slithers from the bed, wobbling slightly as she finds her feet upon the rug. She takes her candle and concentrates very hard on walking across the room without her legs giving out. She feels all over like… like mashed potato. Useless and soft. Boneless. "Goodnight, sir."

She had not realised the ghosts were gone until the moment they come rushing back. As she walks down the hall to the servants' stairs (servant, singular, for it is only her), they blanket out in front of her feet like carpet, puddling over her slippers. They had been quiet as Mr Bridgerton tied her, as if he was, with those clever fingers of his, weaving a net to hold them at bay. But now they are here, fitting into her clothes and threading through her hair and chasing her up the stairs until, panting heavily, she slams the door to her attic chamber hard in their faces.

Hang the ghosts, she thinks viciously, and crawls into bed for a deep, dreamless sleep.

A guinea coin pressed flat upon the kitchen counter, the metal chiming as it hits the wood.

Penelope looks up from her work, her hands sunk into the bread dough she has been kneading for tomorrow's loaf. She had neither seen nor heard the master enter. She looks up at him with her mouth dropped upon. Then down at the guinea. Then back up to him.

She cannot hide her astonishment. He has never once set foot in the kitchens these past three months and he looks ill-at-ease, all his tailored neatness and beauty at odds with the organised chaos of Penelope's kitchen.

"Sir?" She knows she should wipe her hands upon her apron, should curtsy and bow, but the dough is at the sticky stage and there is flour crusted beneath her nails (and, she suspects, upon her forehead) and there seems to be little point in cleaning herself up. "Is there something you should like me to purchase? We do not pay the grocer for another week."

Mr. Bridgerton clears his throat and tugs upon the bottom of his vest. He seems uncomfortable — though he nearly always does. He wears his gentility uneasily, Penelope thinks, which is odd for a man born into the Bridgerton family.

"No," he says stiffly, his chin high. He smooths his palm over his temple, pushing back his tawny grey-and-black curls. "It is for you. For your… service last night." His jaw flickers with discomfort as Penelope's eyes are dragged to the gleaming guinea. More than a month's wages sitting heavily in that fat little blob of gold. "I understand it went… beyond your proscribed duties. You should be compensated duly, I think."

"Sir," she says carefully, her fingers contracting in the bread. In truth she had rather enjoyed herself, strange though it was, and the idea of being paid for such pleasantness makes her skin itch, a pitted feeling in her belly.

Still. More than a month's wages, and for what? Letting her master touch her arm in the candlelight?

She thinks of the extra coin she might send her family in the countryside. She swallows, her throat as thick as if she had swallowed a spoonful of the bread flour.

"And — and if you are amenable, I should like to… continue," he is saying, his jaw still ticking. "I shall pay you, of course, for the imposition. Should you be amenable," he repeats, his right hand fiddling with his chatelaine.

Penelope looks at the guinea, her fingers sinking deep into the sticky dough reflexively.

"Alright, sir." She dips her head. "Yes."

Mr. Bridgerton lays his hand flat upon the wooden counter, his fingertips pressing into the floured surface. The guinea sits in the crescent between his thumb and his forefinger. Penelope feels those blue, crinkling eyes trained closely upon her, leaning close. She hardly dares breathe, her eyes fixed upon the dough spilling around her fingers.

"Good," he says, and his voice is not stiff now, not tense. "Good girl."

He disappears as quietly as he arrived.